-

Executive Committee approves theological education and creation care grants

Continues shaping networks, adding membership and supporting learning and action in member churches Funding for theological education and carbon tax small grants was passed at the annual meeting of Mennonite World Conference’s Executive Committee meeting, 8-11 April 2024 in Curitiba, Brazil. Two new funds For many years, MWC member churches have called for more

-

Every church must plan for succession

Jeremiah Choi, MWC regional representative for North Asia, retired as lead pastor of Agape Mennonite Church in Hong Kong in November 2023. Elina Ciptadi (MWC Interim Chief Communications Officer) sat down with him at the Executive Committee meetings in Curitiba, Brazil, in April 2024, to gather his reflections on this transition period. “The calling has

-

MKC promises memorable and inspirational Assembly

The MWC Assembly in Ethiopia in 2028 takes its first steps toward celebration with the signing of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) and appointment of a national advisory council. From 11-17 January 2024, MWC leaders Liesa Unger (Chief International Events Officer), Sunoko Lin (treasurer), Lisa Carr-Pries (vice president) and Henk Stenvers (president) visited Ethiopia. They

-

One God and Spirit: a bond of peace

“…Making every effort to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Ephesians 4:3). A global fellowship, 109 national churches, 58 countries, some 10 000 congregations, 1.4 million members, 45 languages: can that ever be unified? The church is often called the body of Christ. A physical body needs different organs to

-

Not just a tour; a pilgrimage

Indonesia It was 7 October 2023. Husband and wife Simon Setiawan and Sarah Yetty, members of Jemaat Kristen Indonesia (JKI) church from Indonesia, were in Egypt, leading a tour group of more than 40 people from Indonesia and the United States intending to enter Israel-Palestine. They heard about the Hamas attacks on Israel in the

-

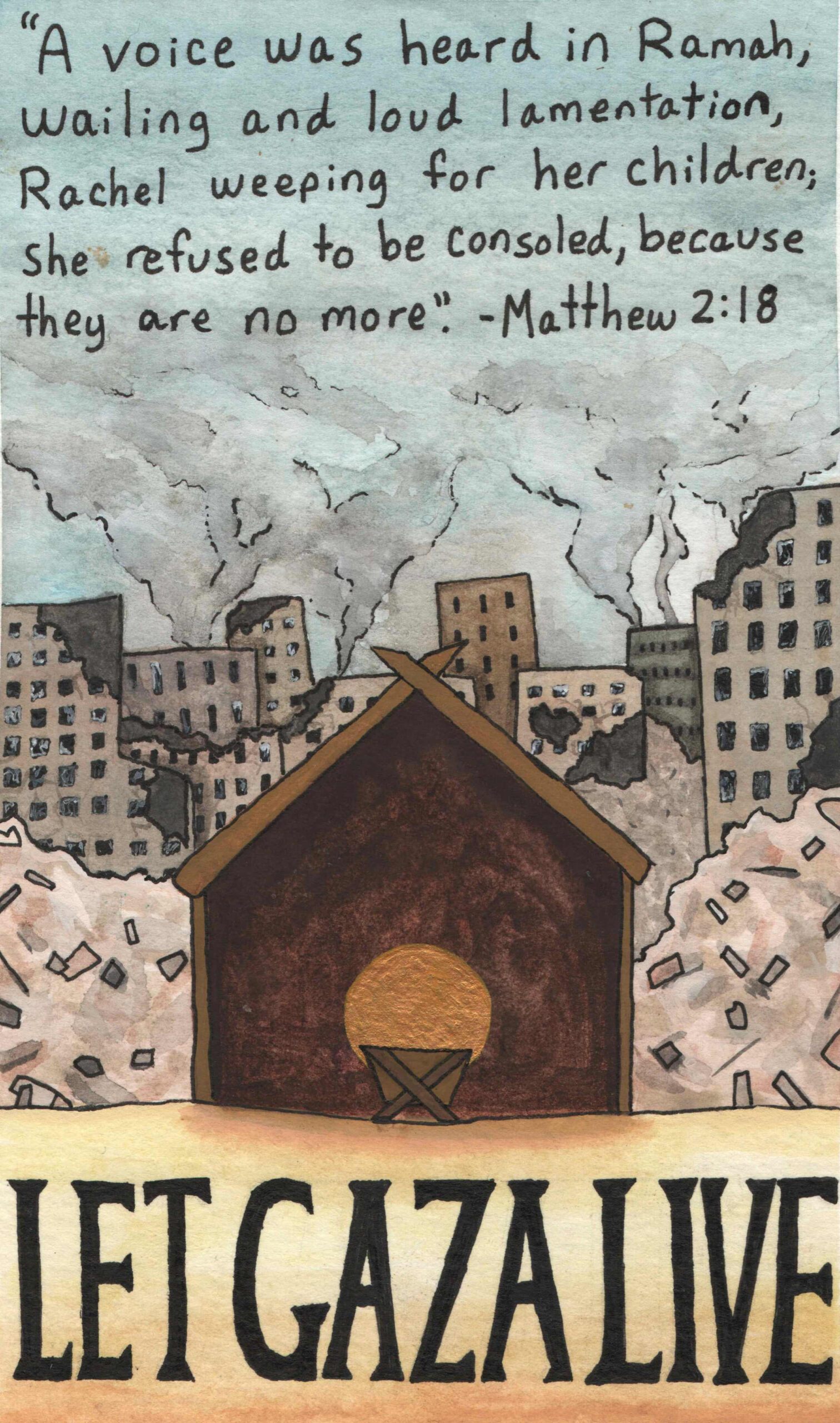

A prayer for peace

Lord, have mercy! Christ, have mercy! Lord, have mercy! When, O Lord, will we learn that peace does not come through force? When, O Lord, will we learn that peace does not come through fighting? When, O Lord, will we learn that peace does not come by conquering others? When, O Lord, will we learn

-

In Memoriam: Reverend Bleise Nzamba (1957-2024)

Reverend Bleise Nzamba, legal represntative of Igreja da Comunidade Menonita em Angola (ICMA), died 30 March 2024. He served Mennonite World Conference on the General Council in Indonesia 2022 and Kenya 2018. Reverend Bleise Nzamba studied at Nyanga College in DR Congo, where he was also baptized in the Mennonite church. In 2013, he graduated

-

A moment to relentlessly seek peace

USA I grew up in Guatemala in evangelical and Pentecostal churches. Our songs, Sunday school teachings and sermons were filled with Christian Zionist theology that declares God’s will to be the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. The duty of Christians is to support Israel. Some churches even display an Israeli flag in their

-

Another way

“There should be justice. They should pay for the terrible wrong they have done.” These and other similar phrases have been repeated in the news in recent months. In my country, Colombia, I have heard the same sentences too many times on the lips of Christians who claim to follow Jesus, the God who chose

-

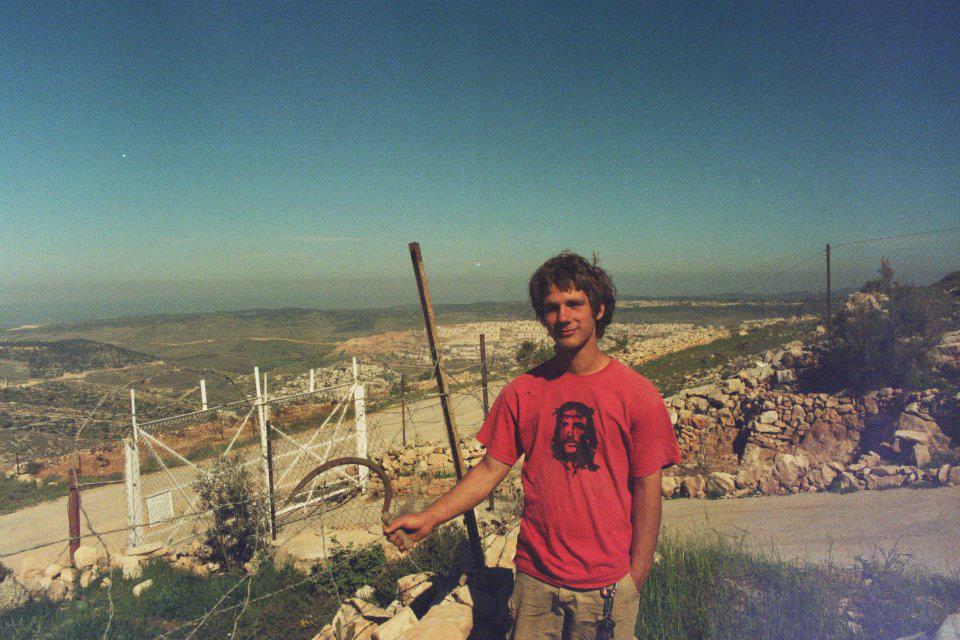

Resistance, repentance and a sweet harvest

It was Palestinian Christians who taught me to see that Bethlehem, Nazareth and Jerusalem are real places whose histories shaped Jesus. His context, plagued by military, economic and cultural oppression, was not so different from the situation of Palestinians growing up today in refugee camps in the West Bank or Gaza. Now as then, injustice…

-

Blessed are the peacemakers

As Christians, we may look to our Bibles to interpret today’s realities in light of long ago promises. The answer to this question is different for each faith community, says Dorothy Jean Weaver. A Jewish community’s answers arise from the Hebrew Bible, but as Christians, we are called to live out of the new covenant…

-

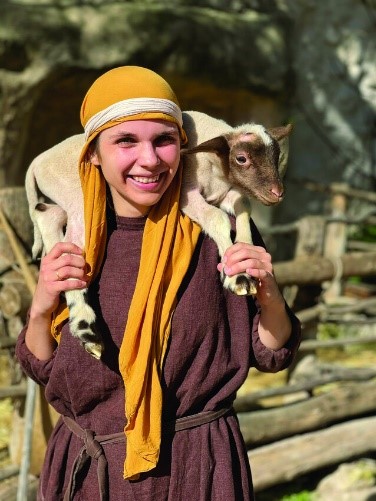

Faith, history and actions

Paraguay My name is Monika. I come from Paraguay, and I did a voluntary service in Nazareth Village. Nazareth Village is an open-air museum in Nazareth, Israel. This museum recreates life of the first century and aims to show tourists the Nazareth of Jesus’ time. I was with the YAMEN* program for 11 months, 2022-2023.