The purple dot on Tanzania on MWC’s global map poster represents two member churches, Kanisa La Mennonite Tanzania (KMT) and Kanisa la Mennonite la Kiinjili Tanzania (evangelical Tanzania Mennonite church). The latter, KMKT, is one of the MWC’s newest member churches. They were accepted into MWC membership at the Executive Committee meetings in Brazil in 2024. Although the church developed by separation from KMT, the leadership had reconciling conversations prior to joining MWC and continue to work at healing the rift. KMKT celebrated their 20-year anniversary in December 2025 with a week of celebration, including MWC president Henk Stenvers as a special guest.

MWC’s triennial map

On MWC’s “Anabaptists around the world” map poster, the countries in the north seem squished, but the size of Africa is roughly proportional to where it needs to be. It’s the Gall-Peters projection which is called an equal area map. Shapes are distorted to keep proportions more accurate. MWC’s statistics have been overlaid atop this map for decades to show countries with Anabaptist churches. Around the world, church bulletin boards are adorned with this visual representation of Anabaptists.

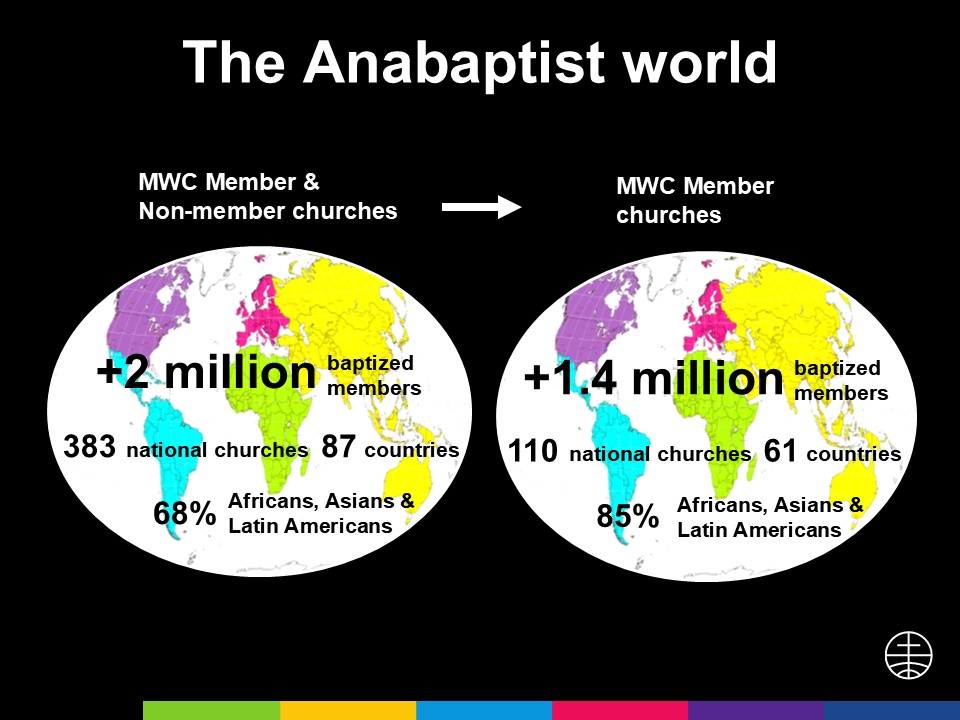

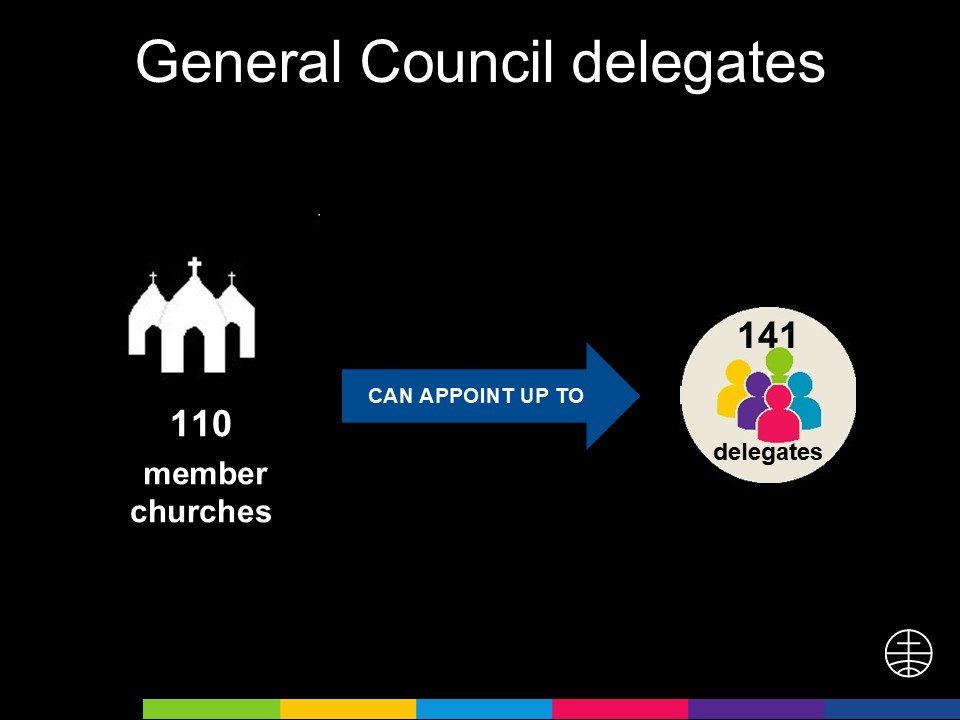

At the beginning of 2026, Mennonite World Conference has 110 member churches (and one international association, IBICA) from 61 countries in more than 10 000 local congregations, speaking more than 45 languages.

On our global map poster, you can see the countries of 2 million baptized Anabaptists around the world.

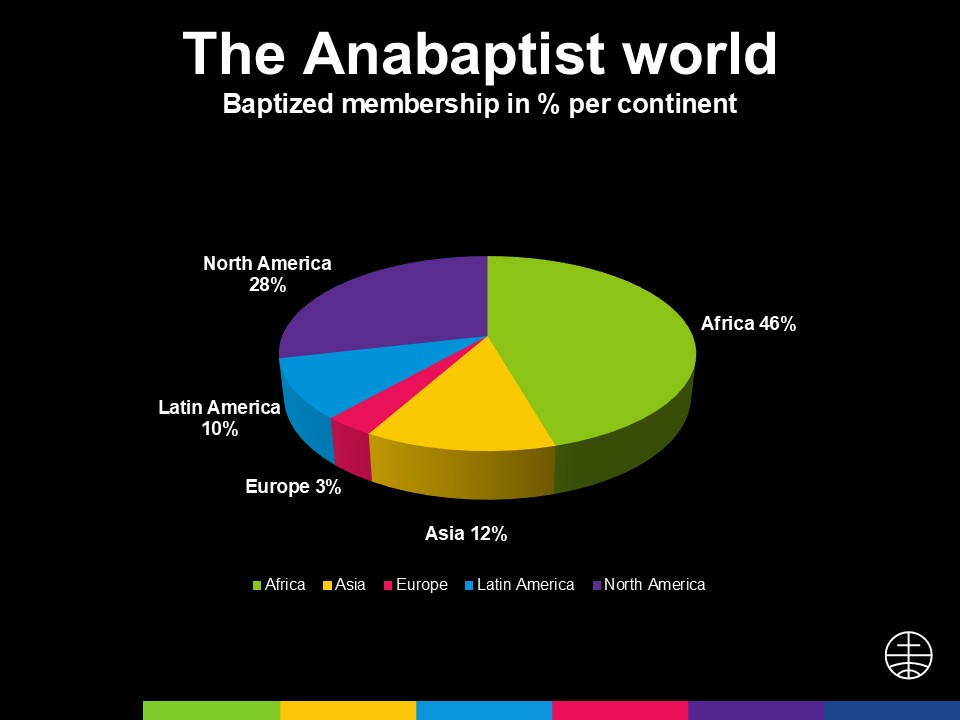

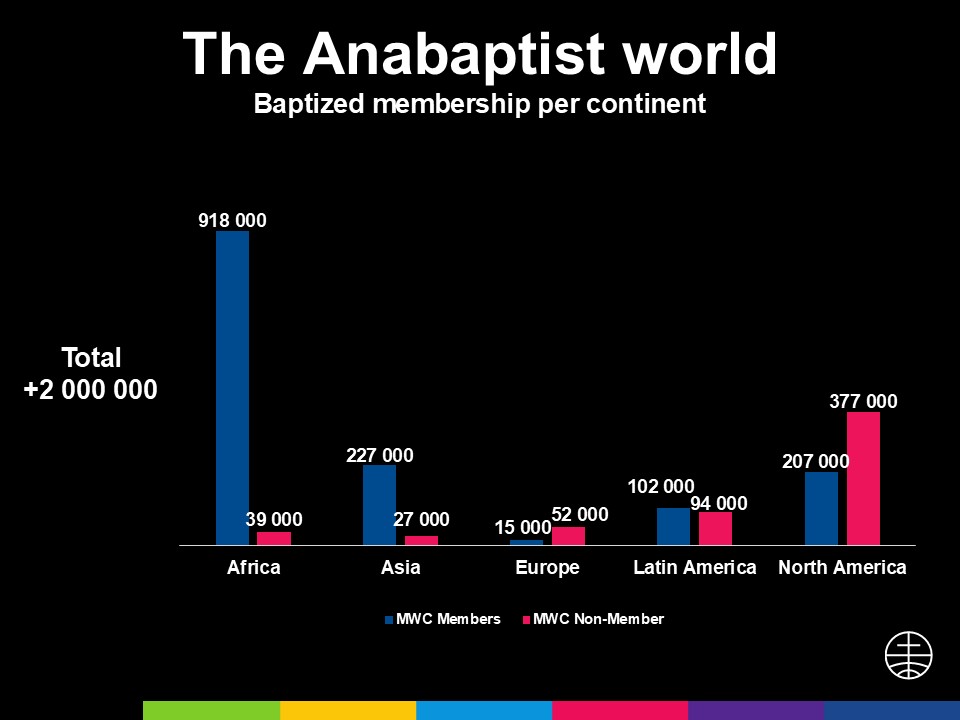

Almost half of all the Anabaptists counted live in Africa, and almost all are MWC members.

Every three years, MWC collates the statistics we’ve collected not only from our member churches but from contacts with other Anabaptist-identifying groups all over.

In North America, where there are large communities of Amish and conservative Mennonites, there are more non-member churches than MWC members.

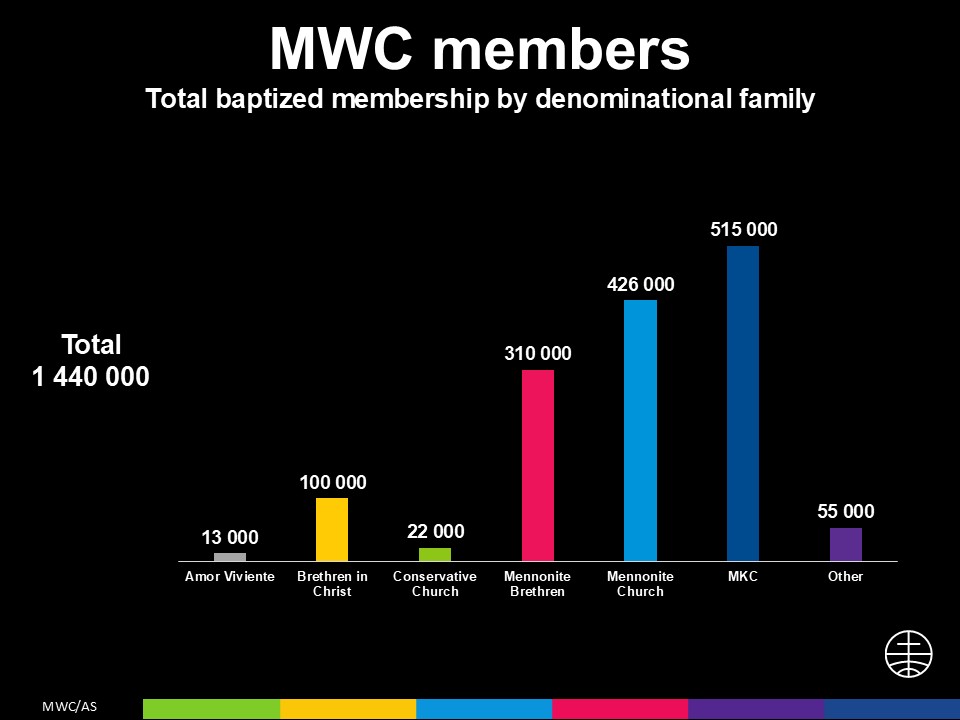

Mennonites and other Anabaptists are organized into about six major denominational families. Meserete Kristos Church which operates in Ethiopia and Eritrea has the largest number of members.

The MWC map is the final step in the process of collecting statistics for membership purposes. Both Fair Share (membership contribution that is indexed to Purchasing Power Parity) and the number of General Council delegates is based on how many members a church has.

“We try to get most current statistics but it’s a long process of tracking down information,” Nelson Martínez, who has collected Anabaptist statistics since 2015 as part of what is now the Communion Building department. At least a year or two before the desired publication of the directory and map, the team begins to work. It starts with sending a letter to all the churches, requesting their information.

But the simplicity ends there.

Response don’t come in on time. Contacts at non-member church may have gone stale.

Churches often update their statics at their General Assembly, which may not coincide with MWC’s due dates. For remote conferences with rural churches spread over a large area, the only way to gather numbers may be from the reports pastors bring to an annual convention. Circumstances from weather to health may prevent a pastor from travelling to the event on a annual basis.

Although the map is intended to represent baptized members, some churches send an estimate of regular church attenders.

Another challenge is the mode: some information comes back handwritten on a document then photographed and sent as an image.

“It can be tricky to understand what they are trying to say. We have to be in constant communication to confirm what we were able to read is the right information,” says Nelson Martínez.

Language can complicate communication. Churches use a variety of words for their organized bodies: synod, conference, etc., so confusion can result at either end about how classify information.

“We try to match our categories to the information they send us. We try to do the closest possible, but it’s not completely accurate,” says Nelson Martínez. “A few churches haven’t responded in years, so we keep the numbers from the last update, but we don’t really know.”

Relationships lubricate the statistics gathering process. Regional representatives are helpful in chasing information when answers aren’t forthcoming. Nelson Martínez also works on travel arrangements for General Council delegates. Friendship develops over the course of working on their travel plans, and it becomes easier to broach conversations about statistics.

After all the statistics have been carefully collected and sorted into parallel categories, the data can be turned into visuals and statistics. Now MWC staff do the creative design work of making a PowerPoint for staff presentations, a directory for General Council members, and the beloved and well-known map poster.

Since the 2025 statistics were presented, Consejo de las Congregaciones de los Hermanos Menonitas del Uruguay (the MB church in Uruguay) removed its membership, adjusting the total number of churches from 111 announced in June 2025 to 110 in 2026.

The 2025 map was redesigned and now comes in two formats: one with circles reflecting church sizes; the other with depth of shading indicating larger or smaller conferences. Both versions show both non-member and MWC member churches all together on the map, with each country’s numbers aggregated across denominational families.

On the website, users can view an interactive map. Statistics can be filtered by continent, country, member or national church. One tab shows the information by baptized members, another presents the circle sizes based on number of congregations.

“We know that both our members and historians and other researchers find the map a useful visual, and the interactive web version a helpful tool. In my interactions with other global leaders, they have also admired our map that presents the global Anabaptist family. We are grateful for our churches’ cooperation with our requests for information so we can share about the global family to the global family,” says César García, MWC general secretary.