-

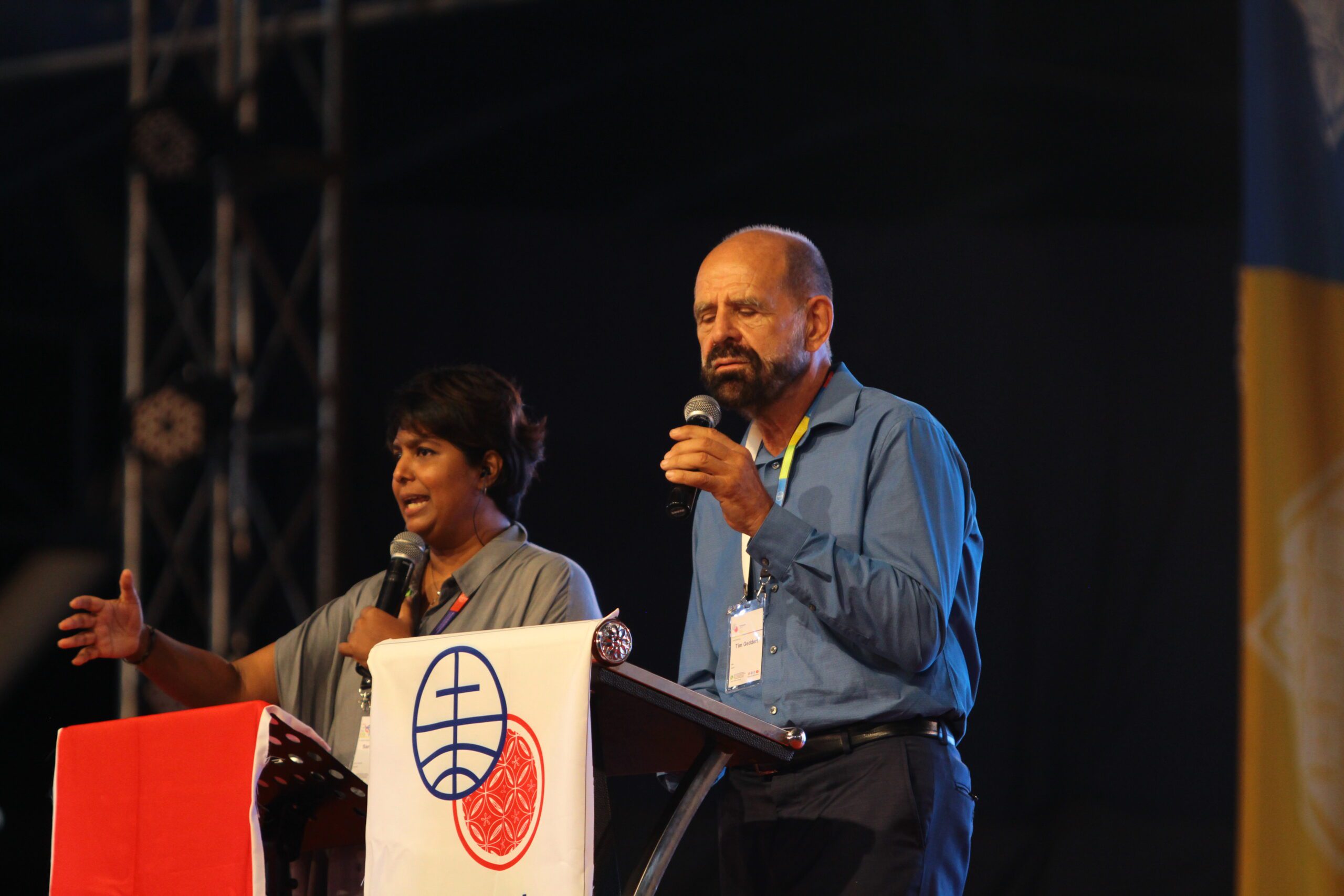

Meet MWC treasurer Sunoko Lin

MWC is a gathering place for each member church to encourage and strengthen each other by sharing resources with one another.

-

The house of God is never finished

It feels like a big responsibility; however, after four years of being president elect, I don’t know if I’m ready, but let’s begin. In MWC, we work as a team: the officers, Executive Committee, staff – we all work together. I feel honoured and humbled to stand in that line of presidents.

-

We are the hands of God in times of crisis

Trust in the power of the Holy Spirit that there is hope in this difficult time. We, as a communion of churches, will be each other’s help in times of need. When the power of the Holy Spirit flows through us you cannot help but take action. The Holy Spirit is our driving force to…

-

A good kind of infidel

“We were far away from peace, but now we are friends with Christians. We are working for peace and humility.” Through an interpreter, Commander Yanni Rusmanto from Solo, Indonesia, spoke at the “Mennonites in Indonesia and Radical Muslims making peace” workshop at Assembly 17 in Indonesia. This was one of several workshops on interfaith relationships…

-

Courier 2022 / 2 October

Plenary sermons Assembly overview Assembly activities Perspectives MWC leaders Resources

-

We speak the same language

“I cannot be grateful enough that even though we are a large and diverse group, we speak the same language: the language of love for Christ and his people,” says Daniel Nugroho. He was part of the team that made it possible for all to understand. Up to four interpreters from a team of 21…

-

Global Youth Summit (GYS)

Life in the Spirit: Learn, Serve, Worship 34 delegates: 4 from North America, 4 from Europe, 11 from Asia, 6 from Africa, and 9 from Latin America. In delegate sessions, some common challenges for young people that surfaced were loneliness and the need for belonging, the need for good leadership, bridging the generation gap and…

-

Learning together to handle diversity

Wednesday morning There have always been two main kinds of learning: academic and experiential. Most of us have an inclination toward one or the other, but the reality is that both are necessary for learning. Knowledge doesn’t do anyone much good if it’s not applied. Alternatively, it’s often counterproductive and wasteful to implement something without…

-

Learning together to discern the will of God

Wednesday morning Learning together to discern the will of God”: the first Christians were confronted with this challenge from the beginning. Indeed, “learning together to discern the will of God” is not mere wishful thinking! It is not a comfortable process. In fact, it is the major challenge of Christian life; of our personal lives…

-

Practice before the storm

Wednesday night When he was 17, my grandfather was forced to fight in World War II (WWII). When I started talking about my plans to study peace and peace theology, he got a little upset. He said: “You talk about peace and war, but you don’t know what you’re talking about! When war comes, you…

-

Puppies and goats are welcome at the table

May we learn from Jesus what God is truly like, crafting a plan to save the world, working in time and space to bring that plan to its glorious fulfillment and pouring out grace on individuals all along the way. May we learn from Jesus what we are called to be, barrier crossers who minister…

-

A fruitful event

Following Jesus together across barriers Mennonite World Conference (MWC) global Assemblies are the equivalent of a Sunday meeting at a local congregation. Through the liturgy, we declare the sovereignty of Christ in our global church, challenging nationalism, racism and other false ideologies that claim our obedience and following. Through teaching, workshops and preaching, we affirm…