France

Association of Mennonite Evangelical Churches of France (AEEMF)

The history of Mennonites in France goes back to the beginnings of Anabaptist history. There were Anabaptists in Strasbourg by around 1526. They were quickly forced to operate clandestinely, but an Anabaptist presence would continue in Alsace throughout the 16th century.

In the 17th century – especially during the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) – Anabaptists from Zurich and Berne settled in the area and contributed to the effort to restore the land to agricultural production. They lived in the Vosges mountains around SainteMarie-aux-Mines and later on in the region of Montbéliard (which was not yet French territory). Since they were rejected by the surrounding society, these Anabaptists lived on the margins, kept their German dialects, and formed “ethnic” communities. Nevertheless, there were ties with other European Mennonites in Switzerland, Germany and in the Netherlands.

In 1693, the “Amish schism” took place among the Anabaptists of France, Switzerland and the Palatine region. Was it necessary to maintain a strict line of separation from the world and practice a demanding form of church discipline? Or had the time come to open up a bit to the outside world? Most French Anabaptists followed the stricter Amish tendency and only adopted the Mennonite label many generations later.

Wars and shifting borders

Having been exempted from military service and the swearing of oaths by the nobles who welcomed them on their lands, these Anabaptists began to experience difficulties starting at the time of the French Revolution (1789). As French citizens, from that point on they were called to participate in Napoleon’s wars. After a respite of a number of years, France forced them into military service.

Around 1850 there were some 5 000 Anabaptists in France and only 3 000 by the end of the same century, the majority of whom were still Alsatian. This majority became German once again in 1870, leaving very few strictly francophone Anabaptists. As a result, the number of Mennonites remaining in France was greatly diminished and toward 1900 some spiritual leaders began to foresee the possibility of extinction.

At the start of the 20th century, the situation of Mennonites in France was not easy. Sixteen congregations had disappeared during the previous century. The remaining families were dispersed and several communities were only able to gather for worship once a month. In addition, there were no ties between the congregations.

Then came the First World War (19141918) where some battlefields crossed the regions inhabited by Mennonites. After the war, Alsace-Moselle became French once again, resulting in an increase in the number of Mennonites. In spite of the war, historian Jean Séguy considers the years 1901-1939 a period of re-establishment and awakening, thanks to a return to Anabaptist history and new contacts with French evangelical (Protestant) churches.

This awakening was interrupted by the Second World War (1939-1945). The region of Alsace-Moselle was annexed by Hitler’s Germany and Mennonite men were forced to enroll in the German army. It is important to note the extent to which French Mennonite history was marked by European wars, from the time of Napoleon to the time of Hitler.

Reconstruction and reconciliation

In 1945, Alsace-Moselle became French once again and two Mennonite groups (French-speaking and German-speaking) began to work together. The presence of Mennonite Central Committee in post-war reconstruction efforts had a very real impact in the lives of European Mennonites, including those in France.

A kind of new life was born, resulting in the start of collective reflection on the questions of nonviolence and conscientious objection; the establishment of social institutions; a new engagement in mission; and the creation of the Bienenberg Bible School. This school had its origins in the reconciliation of Mennonites separated by wars that were still fresh in their memory. Located near Basel in Switzerland close to the French and German borders, it is bilingual (French and German) and trinational.

Until this time, Mennonite congregations in France (now including Alsace-Moselle) were in rural communities for the most part, often made up of farmers (with a very good reputation). Led collegially by elders, preachers and deacons, these congregations had ties between them and important decisions were often made in meetings of elders where all of the congregations were represented in principle. Since the 19th century, worship services in France took place in French, while in Alsace-Moselle the German language and Alsatian dialect had been predominant. From the mid-century on, French became the dominant language in worship and in meetings. Moreover, for more than 20 years, French Mennonites have participated in the Francophone Mennonite Network (Réseau Mennonite Francophone) that aims to create ties among French-speaking Mennonite churches in Europe, Africa and Quebec.

The Alsatian conference and the French language conference merged in 1979 to become the Association of Mennonite Evangelical Churches of France (AEEMF). From that time on there has been a single national structure. Twice a year, delegates from the congregations meet to make decisions on matters that concern the entire group of churches. The annual meeting of elders, preachers and deacons contributes to decision-making concerning theological matters. This structure is somewhere between a congregationalist structure (where each congregation maintains its autonomy) and a synod structure (where churches get together to make decisions for all of them). Within this structure are centers of activity and reflection dedicated to specific questions: youth, ministries, peace theology and ethics, mission in France, mutual aid and development aid and service. Other associated structures, independent of the AEEMF, deal with foreign mission, the publication of a monthly magazine (Christ Seul) and dossiers on thematic subjects (three times a year), hospital chaplaincy, the organization of camps, holiday camps and trips for adults.

Following Jesus through study and service

Until recently in this long history, there was a certain mistrust with regard to the training given in theological schools. Led by a college of elders, Mennonite congregations did not have paid pastors. Certain elders had studied in evangelical Bible institutes in France and Switzerland. Starting in the years 1970-1980 some French Mennonites began to enroll in university theology faculties (departments) in France, or, in rare cases, in North America.

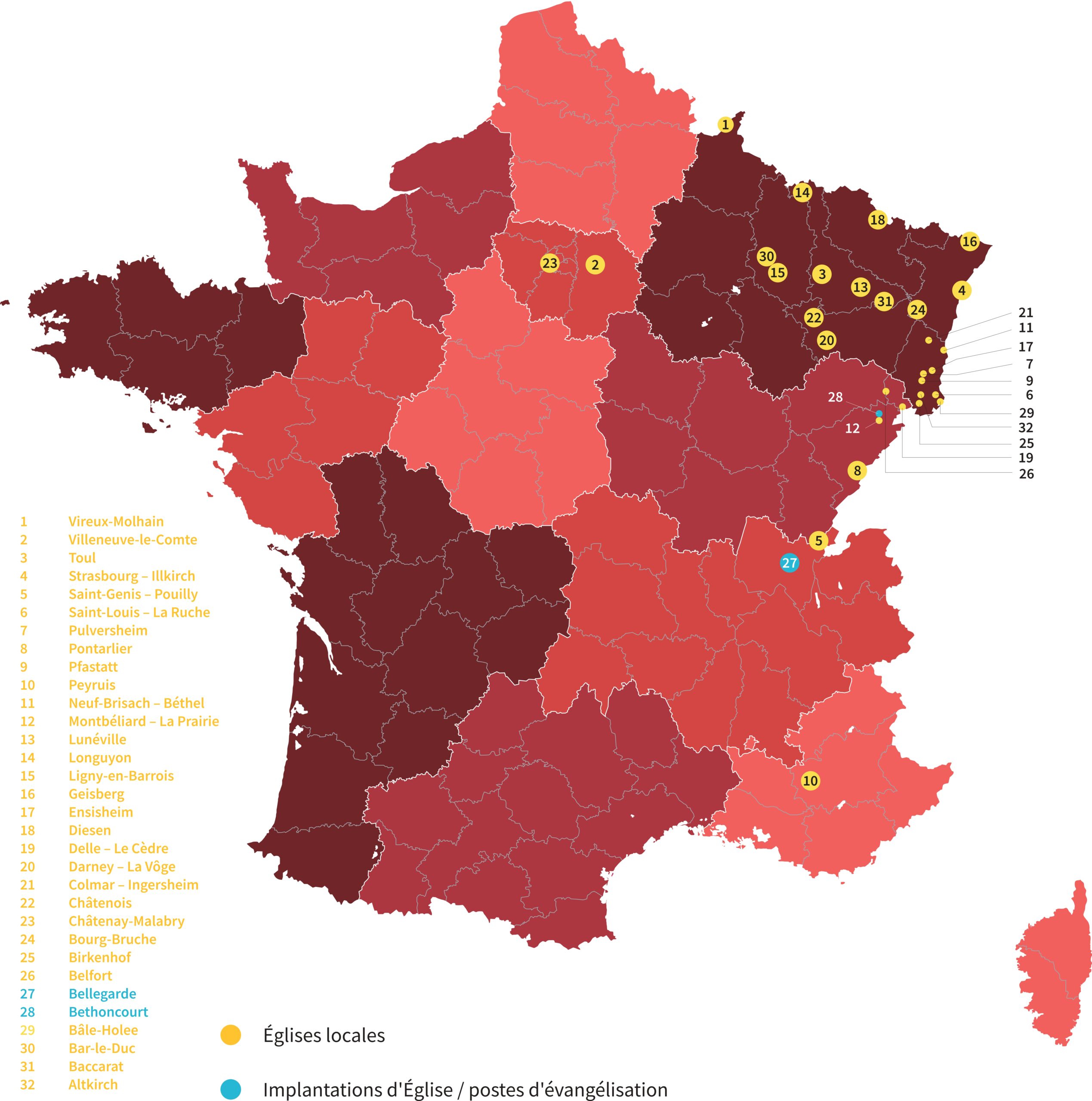

The make-up of congregations has also gone through important changes. Fewer and fewer Mennonites are farmers; many are employed in the majority of professions of the contemporary world. Little by little, the proportion of “ethnic” Mennonites is going down and the number of members of non-Mennonite origin is increasing in the congregations, including positions of leadership. Congregations are becoming less rural and more urban. The first urban congregation was founded in the region of Paris in 1958. Today there are churches in Strasbourg, Mulhouse, Colmar and close to Geneva on the French-Swiss border.

These changes have also resulted in the growing acceptance of trained and paid pastors. A ministries commission helps the churches reflect on the recruitment and hiring of pastors and the importance of maintaining a collegial way of functioning.

Mennonite congregations participate in missionary work outside of France as well as in France, where there are several new church plants in progress. The aid fund engages regularly in humanitarian work, often together with other European Mennonites and with MCC. The presence of the office of Mennonite World Conference in Strasbourg (1984-2011), as well as MCC’s office for Western Europe for a number of years has contributed to showing Mennonites in France the importance of belonging to something global, beyond France and Europe.

French Mennonites recently decided to enter a trial period with the Protestant Federation of France and the National Council of Evangelicals of France, with the hope of becoming a bridge between these two Protestant families.

‚ÄîNeal Blough retired in 2020 as director of the Paris Mennonite Centre. He is professor emeritus at Vaux sur Seine seminary (FLTE) and continues to teach at many theological schools. Didier Bellefleur is a leader in Eglise de StrasbourgIllkirch and president of the Association des Eglises Evangéliques Mennonites de France (AEEMF).