Like the Mennonites (and other Anabaptists) of every country around the world, Canadian Mennonites are rooted in their nation and affected by its history. In global terms Canada is a very large country, spreading 7,000 kilometers from the Atlantic to the Pacific to the Arctic. It is also one of the wealthiest nations in the world, with a strong public education and health support system. It is mostly English speaking, with a strong historical link to Great Britain, although it has a strong French-speaking section in Quebec. As a historic settler society – with farmer immigrants especially in Ontario and in western Canada – it also has a long history of encountering Aboriginal peoples, sometimes violently.

Given its bilingual base, Canada has historically tolerated minority cultures and, especially in the last third of the twentieth century, welcomed large numbers of immigrant newcomers from the Global South. Today, only two thirds of Canada’s 35 million people still identify as Christian (almost twice as many Catholics as Protestants). Eight million Canadians claim no religion at all; about a million identify as Muslim; another million with India-based faiths (as Hindus and Sikhs); and 300,000 each as Buddhists and Jews.

The Mennonites – who are variously counted as between 127,000 (members of Mennonite churches in 2010) and 175,000 (self-identifying in Canada’s 2011 census) – constitute a small minority within Canada. They are also a very diverse group, with more than 20 denominations using the name “Mennonite.”

The Mennonite Church and the Mennonite Brethren

The largest two of these groups are the Mennonite Brethren (MB) and Mennonite Church (MC), with approximately 38,000 and 32,000 members respectively. These two are also among the most urbanized of Canadian Mennonites, noted in particular for attracting large groups of non-Mennonite Canadians, as well as Chinese and Hispanic Latin American immigrants.

The history of the MB congregations stems from 1860 in Russia, when they broke from the mainline Mennonites, emphasizing a personal faith and distinguished by immersion baptism. The first MB congregation in Canada was established in1888 as a mission outpost, but a Canadian MB conference remained small until 1923 when immigrants fleeing Communism in the Soviet Union began arriving in Canada.

The history of the MC congregations is more complex, and consists of the 1999 amalgamation of two denominations popularly referred to as the “General Conference” (GC) and “(Old) Mennonite” (OM) denominations. The OMs formed after the arrival of Mennonites in Upper Canada (later Ontario) from Pennsylvania, first in 1786 but in much larger numbers after 1800.

Although the start of the North American GC in 1860 included an Ontario congregation, a permanent GC presence in Canada began with the founding of the Conference of Mennonites in Canada in 1903, and was further boosted with the immigration of Mennonites from the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1940s. Given their diversity, the MC congregations emphasize unity and fellowship within diversity, as well as social justice programs, especially linked to Mennonite Central Committee (MCC).

Other Anabaptist-Mennonite groups in Canada

Several medium-sized denominations, with between 4,000 and 6,000 members, emphasize an amalgam of Anabaptism and evangelical Protestantism. The Brethren in Christ Church stems from the late eighteenth-century migrations of Swiss-South German Mennonites from the United States to Upper Canada. The Evangelical Mennonite Conference (EMC) and Evangelical Mennonite Mission Conference (EMMC) are both descendant groups of the Dutch-Russian migration of the 1870s, and both shaped by mid-twentieth-century evangelicalism. These groups are noted for both their overseas missions and their support for MCC.

Perhaps surprisingly, 17 Mennonite denominations in Canada – constituting more than 30,000 members – represent “plain” or “old order” groups. These groups rarely seek membership with Mennonite World Conference. They are typically distinguished by simple living, non-conformity and social separation, most apparent in plain clothing, including head coverings for women and long-sleeved, button-up shirts for men. About 20 percent of the most traditionalist of these “plain” people consist of so-called “Horse and Buggy” Mennonites.

Canada is also home to two evangelical conferences (formerly Mennonite Brethren in Christ and Evangelical Mennonite Brethren, now Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada and Fellowship of Evangelical Bible Churches respectively) that have dropped the name Mennonite. Canada also serves as a home for near-Mennonite groups such as the Hutterites and a small number of Amish.

Mennonite institutions in Canada

As for Mennonites elsewhere, the Canadian community is strengthened by a wide range of institutions. In fact, it is quite possible to live in largely Mennonite contexts – especially in rural areas and in cities such as Kitchener-Waterloo (Ontario), Winnipeg (Manitoba), Saskatoon (Saskatchewan) and Abbotsford (British Columbia). Many Mennonite children attend private elementary or high schools. Youth find religious and general university education in numerous Anabaptist-Mennonite post-secondary institutions, most notably Canadian Mennonite University in Winnipeg, Columbia Bible College in Abbotsford and Conrad Grebel University College in Waterloo. Young families can readily obtain loans from a dozen credit unions with significant Mennonite roots: the largest, with four billion dollars in assets, is the Steinbach Credit Union in Manitoba. Fire insurance is offered by several Mennonite-run companies; Mennonite Aid Union, in operation from 1866 to 2002, has been the most historical. Mennonites have even relied on tour packages, such as the Mennonite Heritage Cruise in past years, to organize their vacations, although “Mennoniting your way” has also been popular.

In several cities, Mennonites can seek genealogical grounding at Mennonite archives or remember old times in one of several museums. Wills and bequests are often made through Mennonite Foundation of Canada. In addition, the elderly can find “Mennonite” seniors homes in numerous communities; in Abbotsford, Menno Terrace East, for example, consists of 95 suites on six floors, complete with a wellness center. Several communities feature funeral co-operative or private funeral homes owned by Mennonites.

Mennonites in Canada have increasingly focused on national institutions to support their mission. Ironically, as Canadian Mennonites have become more open to a wider world, they have also become more nation-centric, decoupling themselves from North American institutions. In 1963, for example, MCC Canada was established, distinct from MCC headquarters in Akron, Pennsylvania, USA, thus more able to provide a “unified voice for Canadian Mennonites.” In 1967, the Mennonite Historical Society of Canada was organized to cultivate a unified historical identity, especially with the three-volume Mennonites in Canada history series begun by Frank H. Epp. The 1999 continental amalgamation of the OM and GC bodies to form a unified Mennonite Church denomination carried within its very founding a new division, one along the Canada-USA border, thus birthing MC Canada alongside its United States counterpart. Similar developments describe the MB, EMC, Brethren in Christ and other conferences.

The creation of MCC Canada also allowed for the development of a surprisingly close relationship with provincial and federal governments. In 1975, for example, MCC Canada opened an advocacy office in Ottawa, seeking not only privileges from government but also an opportunity to shape public policy. Indeed, Canadian Mennonites became known for their openness to working with government agencies. The Canadian Foodgrains Bank, founded by MCC, took off in part because of matching funds from the federal government. Then, too, in Canada, an increasing number of Mennonite men and women served in the federal parliament and provincial legislatures.

Themes in Canadian Mennonitism

Over time a number of themes have come to characterize Canadian Mennonite identity. For instance, Canadian Mennonites have created links with Mennonites in other parts of the globe to build a strong global community. They have embraced binational organizations, such as MCC after 1920, Mennonite Disaster Service after 1951 and Mennonite Economic Development Associates after 1952. Historically, MB and MC churches have had close ties to North American overseas missions, especially directed to places in Congo, India and Central America.

Canadian missionaries of particular note include Susanna Plett, who inspired a generation of EMC missionaries when she left for Brazil without church support in 1942. Jacob Loewen of Abbotsford is perhaps the most recognized globally, an MB missiologist noted for ideas of critical self-analysis and indigenous leadership. Christian Peacemaker Teams have transformed the way Canadian Mennonite youth have considered issues of pacifism and nonviolence. Canadian churches have been strong supporters of Mennonite World Conference.

Canadian Mennonites also have learned to express themselves in new ways. Historically they have been singers, with Benjamin Eby producing the first Canadian hymnal in the 1830s and musicians such as Ben Horch of Winnipeg raising music to the level of community choirs and orchestras. They have also been writers, and their ranks include a number of nationally acclaimed authors; Rudy Wiebe’s 1962 Peace Shall Destroy Many is still heralded as a pioneering work. Then, too, “Mennonite” films have become popular: for example, And When They Shall Ask, recounting suffering in the Soviet Union, has attracted thousands of viewers. Finally, numerous web-based resources have arisen, including the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopaedia Online (GAMEO), begun as a project of the Mennonite Historical Society of Canada.

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Canadian Mennonite history has been the story of migration. Seven specific stories of migration are key. The first three recount arrivals in the 1800s, with each group aiming to build exclusive frontier farm communities, all under the protection of the British monarch. These groups included Swiss-American Mennonites arriving in Upper Canada within a generation of the American Revolutionary War; Amish newcomers from Europe in the 1820s; and 8,000 Mennonites of Dutch descent arriving in Manitoba in the 1870s after Russia changed its military exemption laws.

The next two groups came in the twentieth century from war-torn Ukraine and Russia: 20,000 in the 1920s to take advantage of Canada’s relative openness to immigrants, and 8,000 mostly women-headed households after 1948.

The sixth and seventh groups are newcomers from the Global South. Many are Low German-speaking Latin Americans, the descendants of Mennonites who left Canada in the 1920s to avoid English assimilation. Most significant for changing old images of Euro-Canadian Mennonites are newcomers from the Global South who joined Mennonite churches upon arrival in Canada: they include Chin (Burmese), Chinese, Hmong, Korean, Hmong (Loatian), Punjabi (Indian and Pakistani), Spanish (Latin American) and Vietnamese newcomers, among others. Oftentimes these newcomers are refugees from civil war or poverty.

Recent developments

In recent decades Canadian Mennonites have also become open to new forms of worship and church life. Although Janet Douglas Hall was much ahead of her time when she pastored a Mennonite Brethren in Christ church in Dornoch, Ontario, in 1886, she was a forerunner to women who have increasingly served as senior pastors, first in MC churches in the 1970s, and more recently in MB, EMC and Brethren in Christ congregations.

Some churches have embraced informal leadership, including multi-site house churches such as Pembina Fellowship in Morden, Manitoba, or those without a paid pastor, such as Fort Garry Mennonite Fellowship in Winnipeg. The Meeting House, a large Brethren in Christ congregation at Oakville, Ontario, is a “church for people who aren’t into church” and meets in movie theatres located in multiple locations that are linked by video connections. Other congregations, such as the Toronto United Mennonite Church, part of the MC denomination, are noted for “welcoming” members of the LGBT community.

Church planting has also been part of the recent story. The MB denomination in particular has experimented with different forms of robust church planting, notably establishing the Églises des frères Mennonites in Quebec. In past decades the GCs in Manitoba sought to reach out to and worship with Aboriginal communities, increasingly in ways that embraced the idea of Creator God.

Finally, many churches have dropped traditional hymnody for more upbeat choruses, aided with PowerPoint projection and live bands. Numerous churches, such as Bakerview MB Church in Abbotsford, however, have at the same time introduced liturgical services, reflecting a growing attraction among Mennonite youth for high-church traditions.

Royden Loewen is chair in Mennonite studies and professor of history at the University of Winnipeg (Manitoba, Canada). He wishes to acknowledge the input of Marlene Epp, Bruce Guenther, Mary Ann Loewen and Hans Werner in the writing of this article.

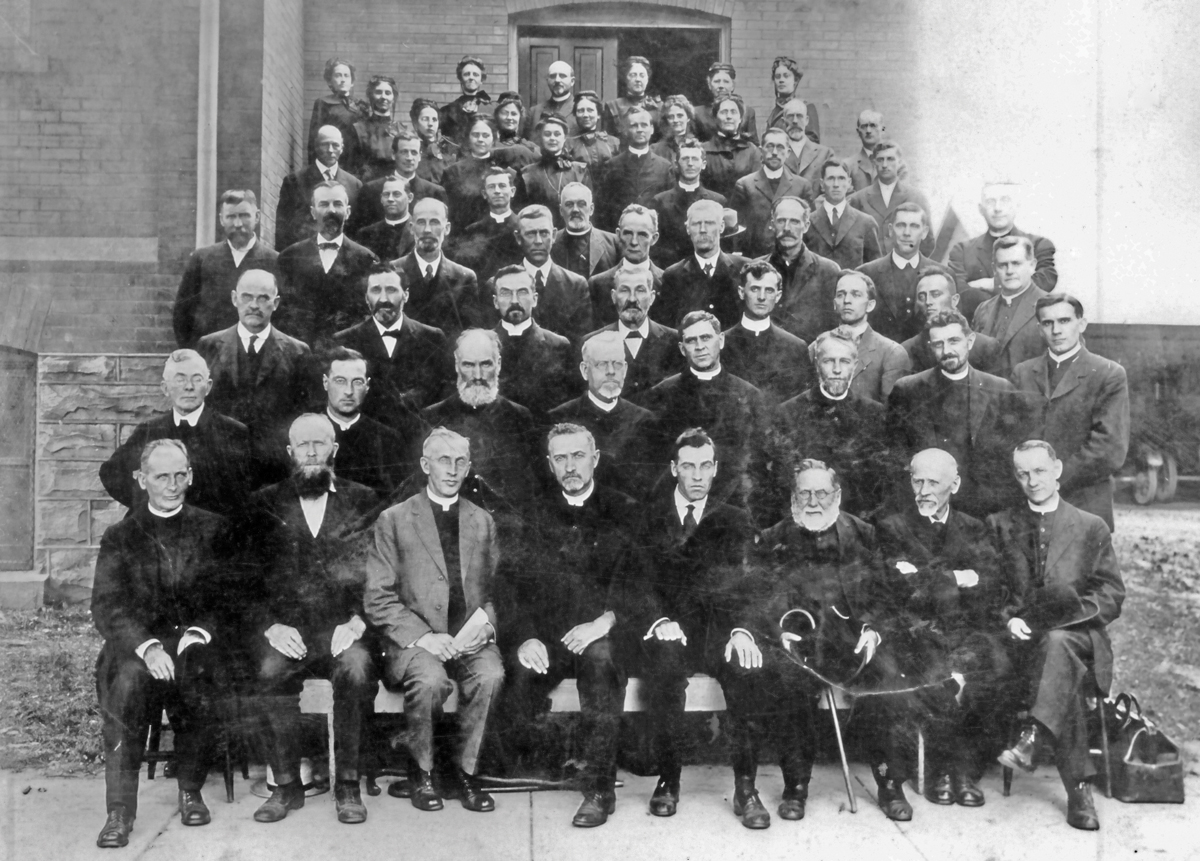

Ministers and leaders attending a 1917 gathering of Mennonite Brethren in Christ in Kitchener, Ontario. Today, after several mergers and name changes, this group is known as the Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada. Courtesy of Mennonite Archives of Ontario

Leaders of Hmong Mennonite Church (Kitchener, Ontario) in 1991, from left to right: Ge Yang, Toua Jang, Lee Xong, Tou Vang. Increased ethnic diversity has been one of several recent developements in the history of Canadian Anabaptists. Photo by Larry Boshart/Courtesy of Mennonite Archives of Ontario

As part of the work of Mennonite Central Committee’s relief program, which provided food and material aid for disaster-stricken areas, Alice Snyder labels Christmas bundles for international distribution in 1954. Photo by David Hunsberger/Courtesy of Mennonite Archives of Ontario

Updated 9 March 2022: photo removed.