-

Peace Sunday 2021 – worship resource

Click below to download Theme: Finding hope and healing in crisis Why this theme was chosen: In these gospel passages, Jesus brings salvation in the midst of crisis. We desire and need this peace, especially after this year! And as followers of Jesus, we follow his example and work to bring peace in the midst

-

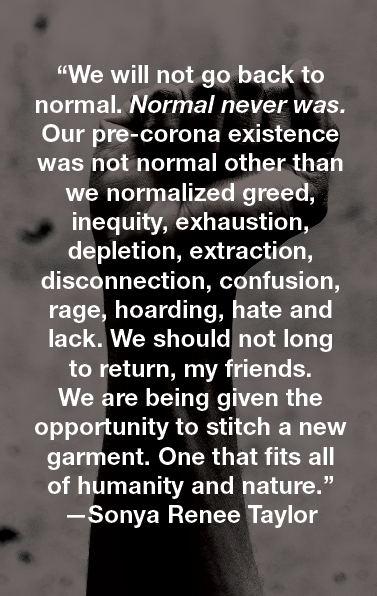

Solidarity and our interconnectedness

As I write these words, our world is embroiled in several struggles. First, we have been clutched by a global pandemic which has disrupted any sense of normalcy we may have assumed. Our second struggle is with overt expressions of deeply rooted racism that continues to kill and oppress black and brown brothers and sisters.

-

Peace Sunday letter 2020

19 June 2020 Dear brothers and sisters in Christ, Greetings to you in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, our Prince of Peace! We write to invite you and your congregation to observe Peace Sunday together with brothers and sisters in the global Anabaptist church family on 20 September 2020. Accompanying this letter, we

-

Peace Sunday 2020 – worship resource

Theme When one member suffers, all members suffer: Peace as accompaniment and solidarity If we are interested in embodying God’s peace and justice in this world, what happens to one affects and should also matter to others. Biblical text: 1 Corinthians 12:12–27Ruth 1:1–17Ephesians 4:1–6Galatians 6:1–5 Additional resources in this package Additional resources available online:

-

“A peace that passes all understanding”

Sermon notes for Peace Sunday Background to the Letter The Writer This is a profound letter written by Paul. Rarely do we take the time to think about the conditions under which this letter was written in Philippi, but it is important to analyze the context of the author a bit in order to understand