-

More united than ever before

Alfred Neufeld, chair of MWC’s Faith and Life Commission, reflects on the state of the global Mennonite faith community Alfred Neufeld, theologian, historian and generally insightful philosopher, reads on two tracks these days: “Proceedings” from past Mennonite World Conference Assemblies and social media. Neufeld, of Asuncion, Paraguay, is on a year’s sabbatical from his administrative…

-

“Nothing that I am doing am I doing by myself”

Rebecca Osiro of Nairobi, Kenya, steps into her new role as vice president of Mennonite World Conference (MWC), with a life of experiences that has tested her faith and taught her wisdom. Rebecca was the first woman to be ordained in the Kenya Mennonite Church (in August 2008), but her interest in the church stretches…

-

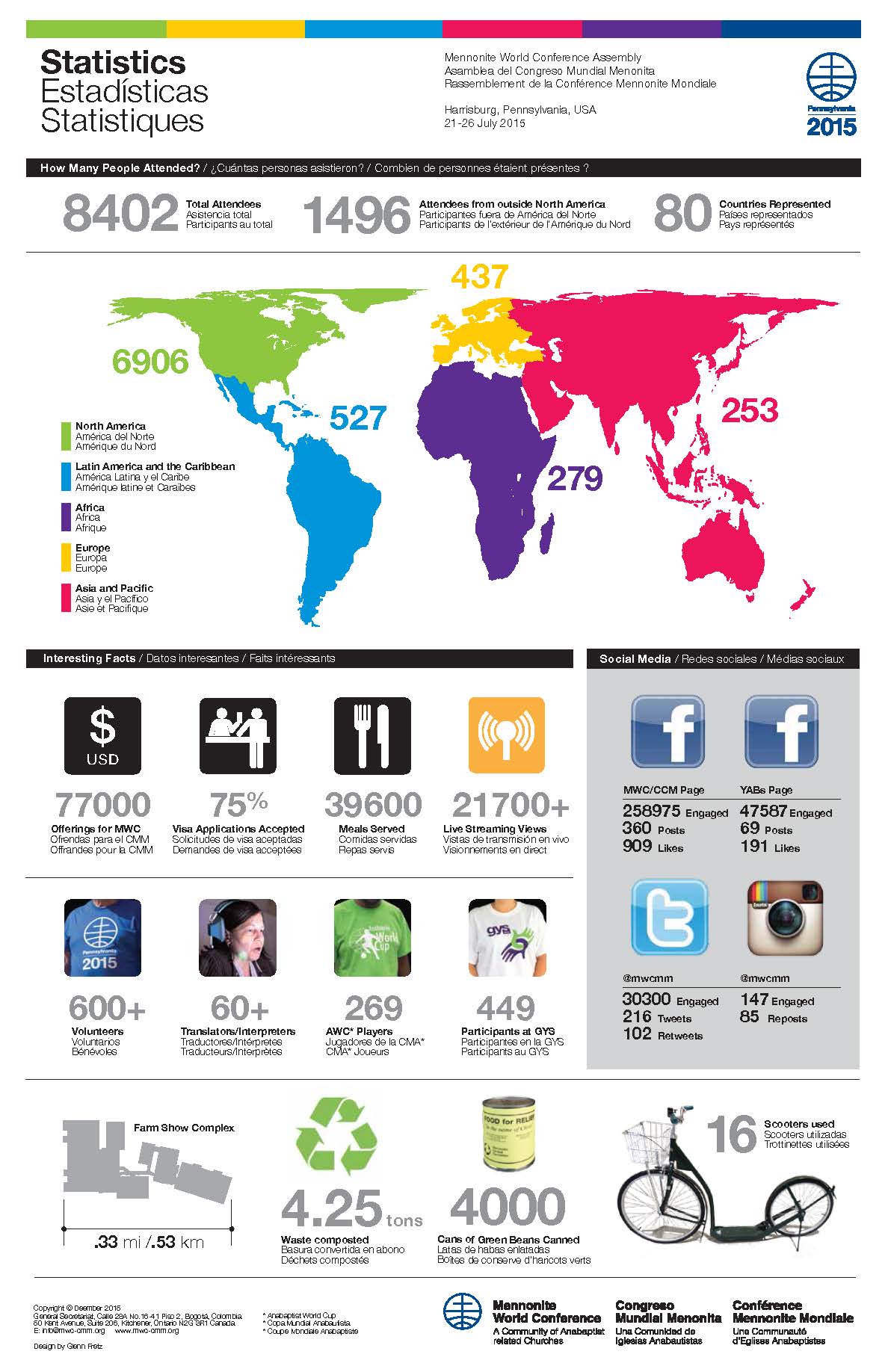

PA 2015 by the numbers

Bogotá, Colombia – Mennonite World Conference’s (MWC) 16th Assembly in Pennsylvania, USA, connected Anabaptists from around the world, in person and electronically. A new statistics poster released by MWC illustrates the final numbers from PA 2015. There are many interesting facts, for example: 75 percent of visa applications were accepted and 4.25 tons of waste…

-

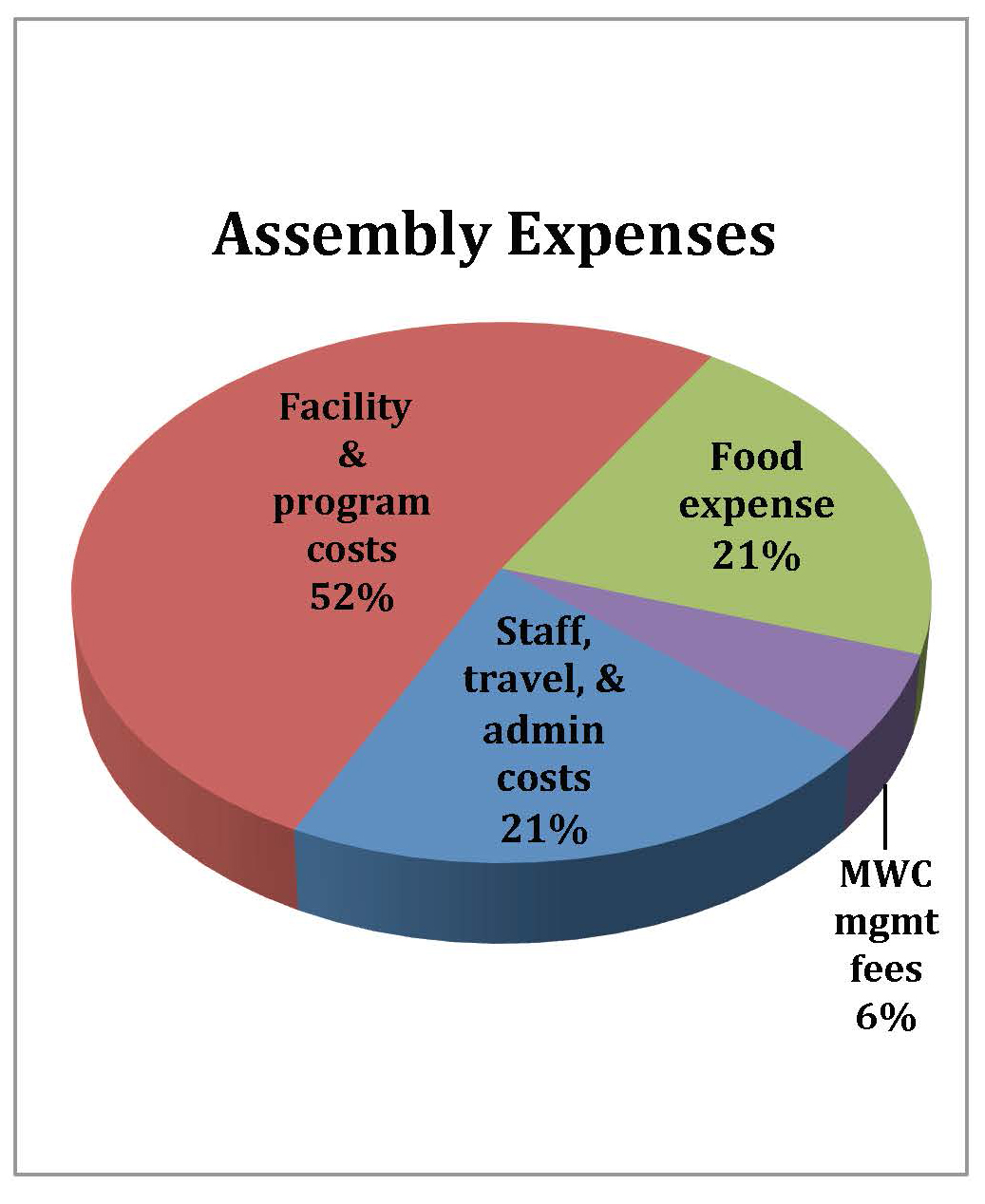

MWC Assembly balances books

Bogota, Colombia – Assembly PA 2015, the once-every-six-years gathering of Mennonite World Conference, closed financially at break-even, that is, without a deficit. The MWC operations team continuously made adjustments, maintaining priorities of environmental sustainability and financial stewardship despite unexpected developments. The net total income of $3,300,000 USD from registrations and donations (adjusted for transfers to…

-

Courier 2015 / 4 October

Author advisory PA 2015 plenary speaker Bruxy Cavey resigned 3 March 2022 from The Meeting House, Oakville, Ontario, Canada, a member of Be In Christ Church of Canada, MWC member church. The congregation’s Board of Overseers requested his resignation after a third-party investigation determined he had a sexual relationship that “constituted an abuse of…

-

A Vision for Reconciliation

How did you become interested in the life of the church? Kraybill: Growing up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, USA, my family was deeply involved in the mission of the church at the local level. Both of my parents gave tirelessly to the congregation, serving in many roles, from Sunday school teachers to janitors. My uncle Nevin…

-

Walking in Autonomy and Community

How to be independent together In the beginning, man was alone. Even though God created all animals and brought them to man to be named, man was alone. And it didn’t suit him at all. God could see that, and so he whispered a deep, deep sleep unto man and while he slept, God took…

-

Why do we need a global communion?

“Walking with God” is the theme of our next global Assembly, to be held 21-26 July 2015. But how can we walk together if we do not believe exactly the same? That was the question that a leader raised some months ago while I was visiting his community. He believed that it is not possible…

-

A New Pattern of Leadership

“Colombian people do not fight for money. You fight for power.” These were the words of a North American missionary after several decades of ministry in Colombia. She was speaking about the ongoing reality of broken relationships among church leaders because of conflicts. After 22 years of ministry in Colombia I must recognize that this…

-

It Takes a (Global) Village: Being the people God wants us to be

When someone asks you to use a few words to describe yourself, what words do you use? Would you change those words to describe yourself when you are with your family? At work? Travelling to some distant place? I discovered that the words I use to describe myself change, depending on my cultural context. When…