-

Global Communion and why it matters

Exploring our shared commitment to being a worldwide family As Mennonite World Conference, we share a commitment to being a worldwide communion (koinonia) of faith and life. Together, we seek to be a fellowship that transcends boundaries of nationality, race, class, gender and language. Yet because of our diversity, each MWC member church brings a

-

The United States: Diversity, dynamism and paradox

A context for Anabaptist witness The United States was formed, in 1776, as the first modern republic. Its founders believed they were engaging in a pioneering political experiment and granted relatively generous freedom of conscience to diverse Christian groups. It was also a nation in which, until 1865, at least 12 of every 100 people

-

Walking with God

I was 17 years old when an army captain asked me, “What would you do if our battalion was attacked tonight? What would you do if someone came and shot you?” “I would pray,” I responded. At that instant, I felt a sharp pain on my head. The captain had hit me with a lyre

-

Walking in Doubt and Conviction

The Holy Spirit’s mercy irons us in our trials “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ!” (1 Peter 1:3). Peter begins this letter with praise to God. This praising to God is a celebration of worship. This expression of blessing to God is found very often as doxologies, especially in psalms.

-

Walking in Conflict and Reconciliation

Light and hope for those in darkness Today, world security is threatened by international, intertribal and even interreligious conflicts. Sometimes, security forces have conflicts with the very people they are supposed to protect. Terrorism has created a climate of insecurity on the international level. Countries are torn apart by wars. Political-religious movements such as Al-Qaeda,

-

Walking in Receiving and Giving

Author advisory (below) “Rock on”: Fulfilling the bidirectional royal law We are a peace church because we are first and foremost a Jesus church and Jesus leads us in the way of peace. We care about justice because we care about Jesus and he cares about justice. We care about reconciliation and we care about the

-

Evening Sermons from PA 2015

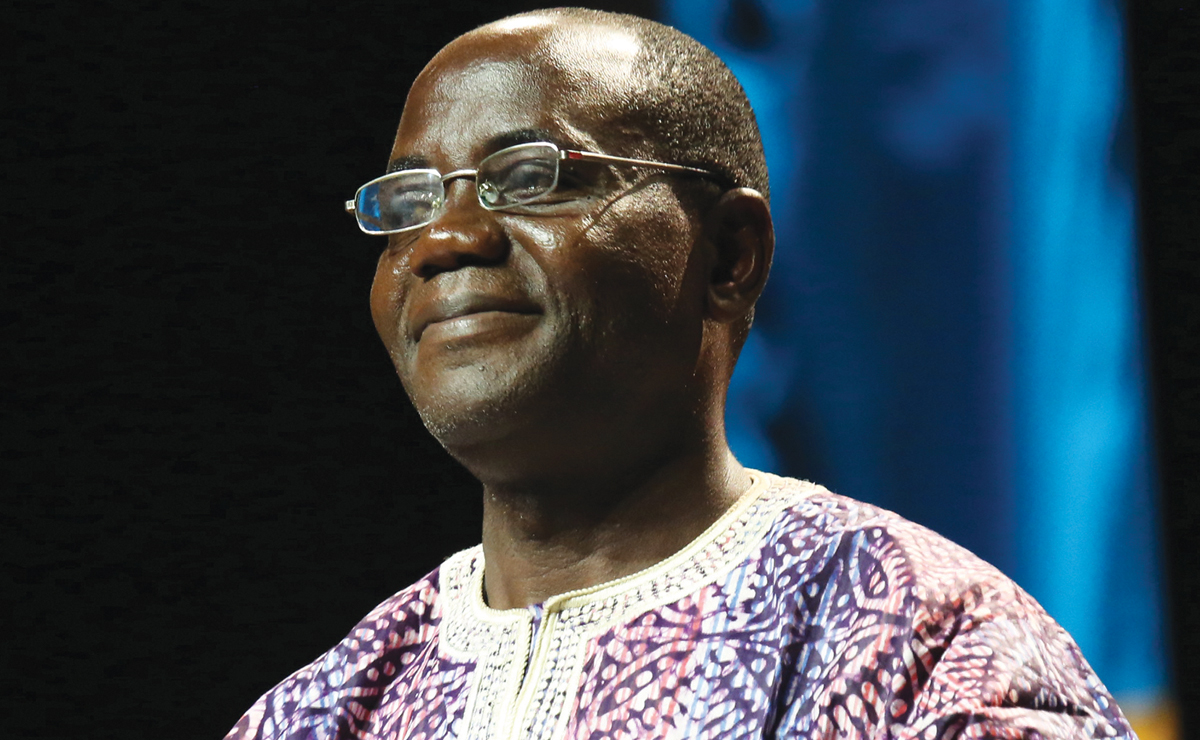

Read the full text of the evening sermons from PA 2015, by César García, Yukari Kaga, Nzuzi Mukwa, Wieteke van der Molen and Bruxy Cavey. These can also be a helpful resource as you prepare to celebrate World Fellowship Sunday with your congregation. Evening Sermons from PA 2015 Walking with God (César García, Colombia) They discovered that

-

Children of light

Some of us remember that the term “Anabaptist” was first of all an insult. This word, literally meaning “rebaptizers,” belonged to the arsenal of other insults hurled at our ancestors. Not by pagans or Muslims, but by other Christians in Europe. They called us enthusiasts, heretics, seditionists and blasphemers. Our forebears were able to give

-

God walks with us

Tom: We walk with God in both doubt and conviction. Both are part of our walk of faith. After all, as Hebrews 11:1 reminds us, “faith is the reality of things hoped for, the proof of things not seen.” As Paul says in 1 Corinthians 13:12, if we see at all, it is “through a

-

Doubt sharpens our convictions

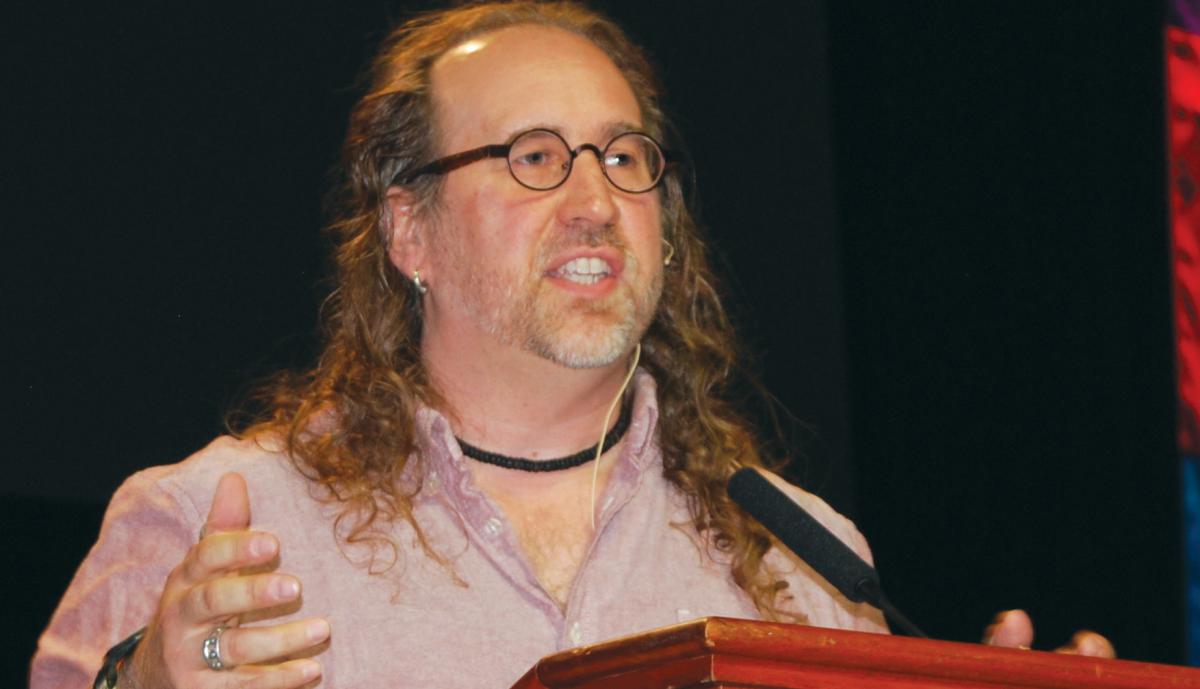

The organizers of this conference were so gracious that they did not impose a topic, rather respectfully provided me an opportunity to select from a range of themes. As you all know, making choices from choices is a difficult choice, but not this time. Without doubt, I picked “Walking with Doubt and Conviction.” Choosing doubt

-

Soldiers in the army of the living God

Ephesians 4:1–7 On behalf of our brothers and sisters from Integrated Mennonite Church in the Philippines, as well as churches across Southeast Asia which I represent as a YAB speaker, I’d like to greet you a hearty, “Good morning!” It was also in July, 10 years ago, when I said good-bye to this country where

-

Repentance and forgiveness

Greetings to my Anabaptist brothers and sisters. Thank you for having me and thank you for coming. It is a righteous joy to be together. I live only 45 minutes from here in a city called Lancaster, which some of you may have heard of and many of you may even be staying this week.