-

A rush of violent wind

Three reasons the Holy Spirit is relevant to the church today Fifty days after Passover, the Jewish community gathered in Jerusalem for the Festival of Weeks. At the same time, the followers of Jesus gathered in a room awaiting the promise of the Holy Spirit. As they were waiting, “suddenly from heaven there came a

-

The gift of the Holy Spirit in the 16th century and today

Many written testimonies of the early Anabaptist movement point toward the work of the Holy Spirit as the central driving force. The Holy Spirit goes to people who are awaiting. It was the case in Pentecost (Acts 2) while the disciples were praying; it was the case in Reformation times; and it is the case

-

At peace with the land

Is there a way to make a living without killing the environment? For a country that sees thousands of deaths every year due to exacerbated effects of super-typhoons, this is a major question. Lives have been claimed and billions worth of infrastructure have been damaged due to intense floods and landslides brought by forest denudation,

-

A Countercultural Lifestyle

“The plane! The plane!” This was how a TV program began that I used to watch as a child in Bogotá. It was about an island where all the desires of those that arrived there would be fulfilled. In English it was called Fantasy Island. It is possible to live on Fantasy Island right now,

-

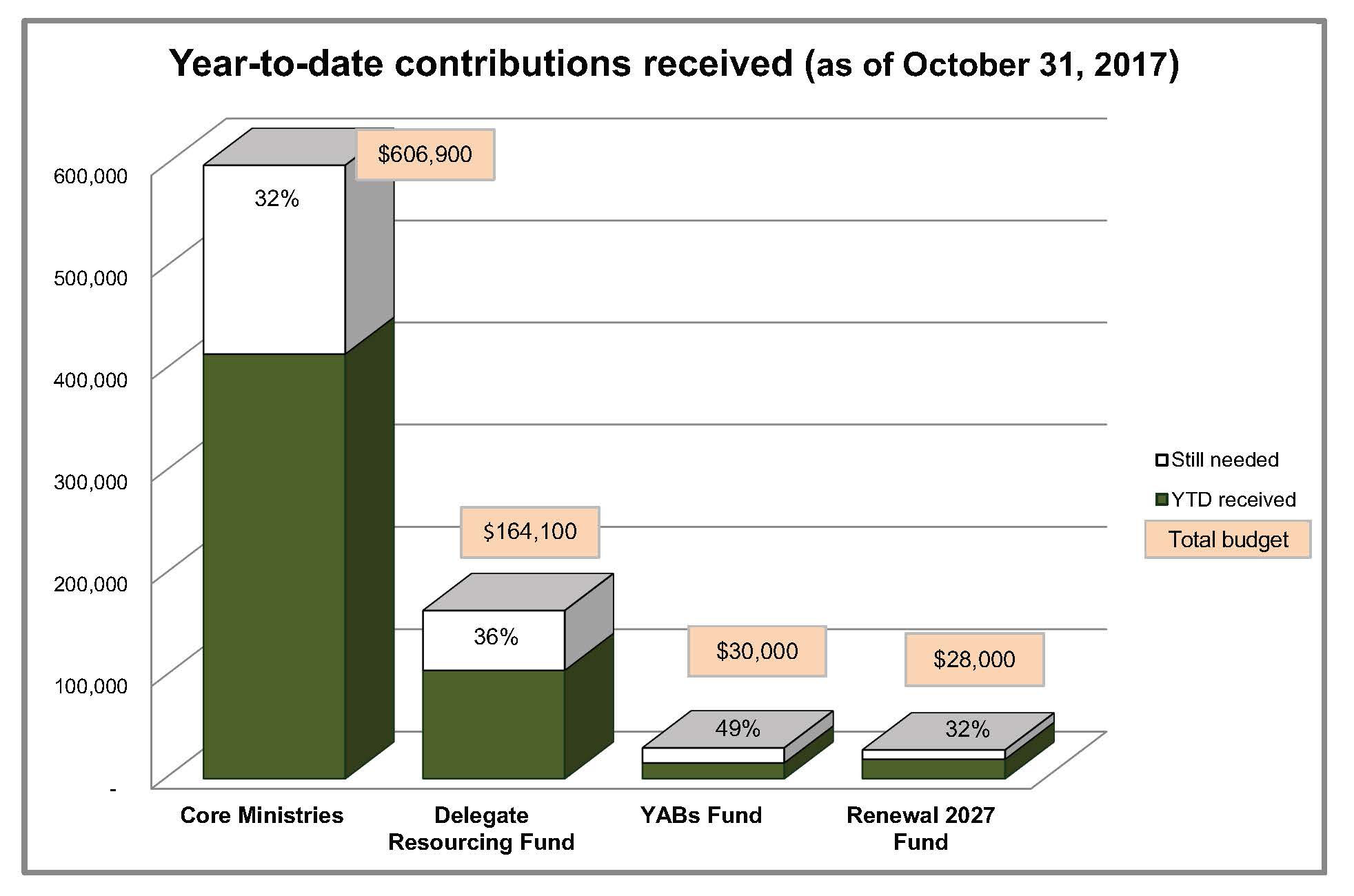

MWC financial update

Bogotá, Colombia – We are grateful for the steady flow of contributions in support of Mennonite World Conference, whether from our national member churches, local congregations, or individuals. We are somewhat surprised that giving is slower this year than average, resulting in being behind budget at the end of August. Contributions from individuals and from

-

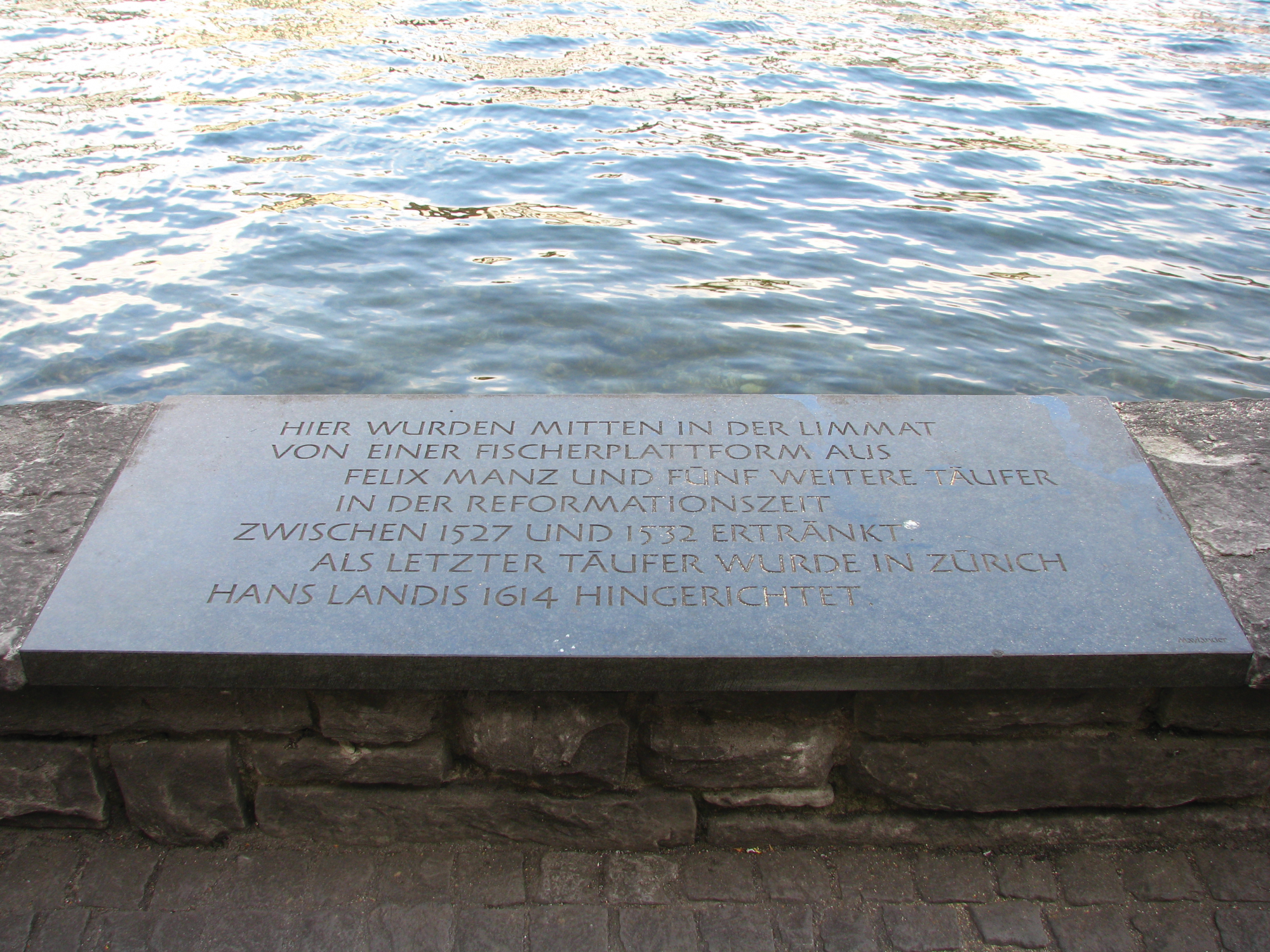

Persecution past and present

Early Anabaptists in Augsburg, Germany, paid a high price for meeting at the large white house (left) in this picture. German Mennonite historian, theologian and peace activist Wolfgang Krauss retells the story to modern Anabaptists who toured historic sites in Augsburg during meetings of Mennonite World Conference Executive Committee in February 2017. On Easter Sunday

-

You will be my witnesses?

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.” At Renewal 2027 – Transformed by

-

Evangelism in action

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.” At Renewal 2027 – Transformed by

-

Systematic disciple making

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.” (Matthew 28:19–20) At Renewal 2027 –

-

Everyone is called

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.” At Renewal 2027 – Transformed by

-

Taking action for your neighbourhood

There is a saying that you don’t know what you have until you lose it. I would add “or until you see the real and present danger that you could lose it.” Something similar happened to our natural resources. For a long time, we had accessible clean water, pure air to breathe and clean and

-

Churches together for climate justice

“Climate Justice Now!” “People Power!” “Keep it in the ground!” echoed through the corridors as I walked through the Blue Zone – the place where 197 member-states of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) gathered in December 2015 to decide on the future of our climate. It was the first time that