Mennonite World Conference has no formally associated Anabaptist member churches in the Middle East. This was a missiological decision not to start another church in a region replete with variety.

However, Palestinian Christians are a witness to the Mennonite communion around the world. Where theory meets reality, they have shown those who are paying attention what it is to be faithful to Jesus’ call to nonviolence.

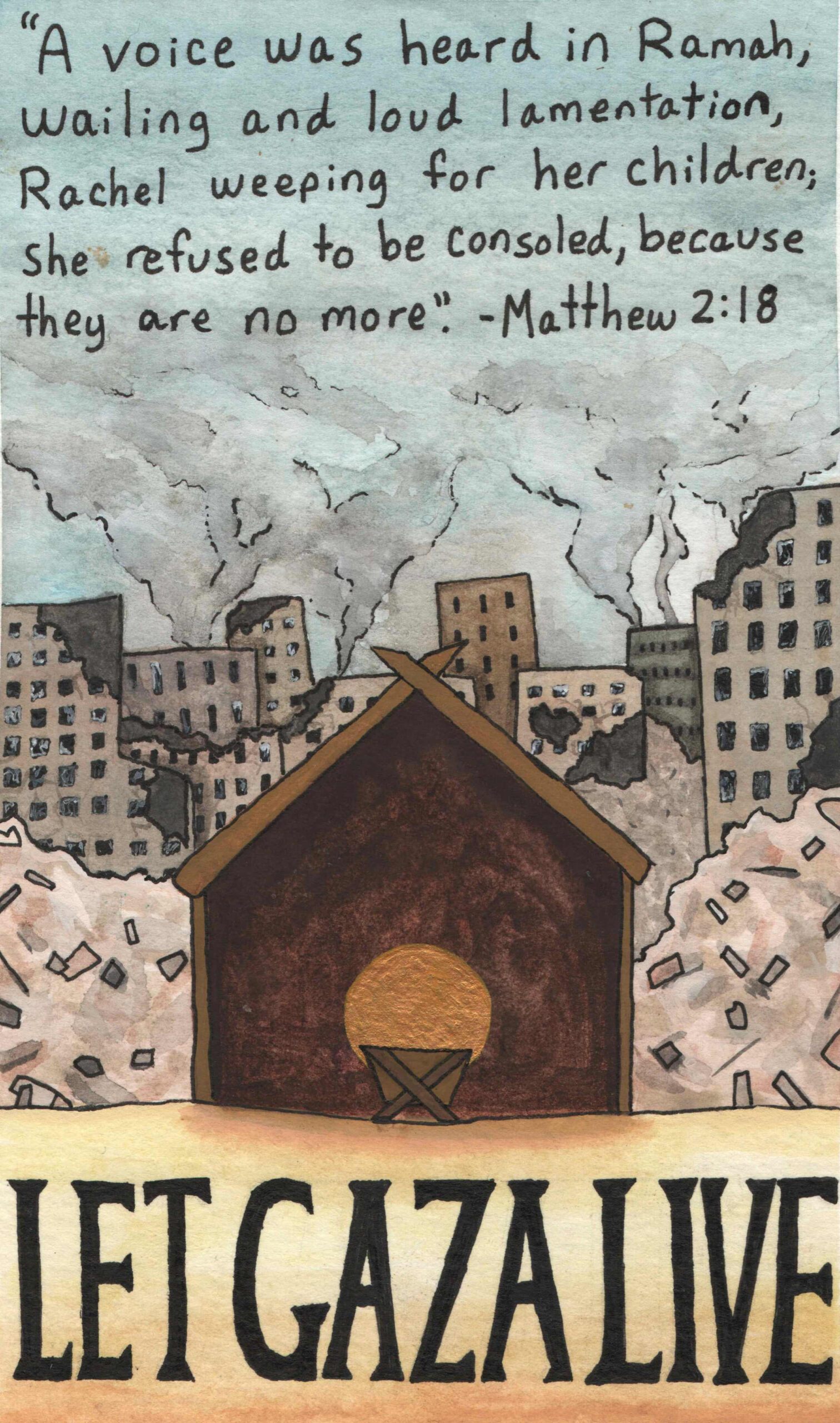

Since 7 October 2023, the eyes of the world have been turned to the Middle East where an act of violence and violation has unleashed a flood of death and destruction.

As Christians, we may look to our Bibles to interpret today’s realities in light of long ago promises.

The answer to this question is different for each faith community, says Dorothy Jean Weaver. A Jewish community’s answers arise from the Hebrew Bible, but as Christians, we are called to live out of the new covenant where geography is “no longer a factor for the disciples of Jesus.”

She joined several Mennonite scholars with experience in the region to reflect on what we read today.

A trajectory of inclusion

Starting in Genesis 12, we see the trajectory of inclusion that can be followed throughout Scripture, says J. Nelson Kraybill. It speaks of blessing and cursing but of these coming through the people of Israel to others.

“In Amos 9:7, God frees not only the Israelites, but also other people, even those who are considered the enemy of Israel,” adds Paulus Widjaja.

“One of the themes that comes through in the Old Testament in passages like Leviticus 26 or Jeremiah 7 is that covenant with God’s people is contingent upon acting justly,” says J. Nelson Kraybill.

“Jesus then picks up on Isaiah’s vision of all nations streaming toward the mountain of the Lord’s house (Isaiah 2:2) when he says the Temple Mount is supposed to be a house of prayer for all nations (Matthew 21:13),” says J. Nelson Kraybill.

Matthew (which is a very Jewish Gospel) ends with the disciples leaving Jerusalem, leaving Galilee and going to make disciples of all the nations, says Dorothy Jean Weaver.

And the very same thing happens in the Gospel of Luke. There’s a lot of focus on Jerusalem in the early story of Jesus, but by the end and even more so in Acts, “the gospel is moving from Judea to Samaria to the ends of the earth,” says Dorothy Jean Weaver

A different framework

There is sometimes a problem of ignorance even among some Christians, says Paulus Widjaja. “The Israel in the Bible and the modern State of Israel are two different things. We cannot just bring it together as if the modern Israel is the biblical Israel.”

“What makes me sad is that what has been created today is hatred, not love. Both Israelis and Palestinians have become victims,” says Paulus Widjaja.

“According to Leviticus, the land is God’s – people are tenants and aliens in the land,” says Alain Epp Weaver. This applies whether talking about Israel or North America or any place.

“Remember, as Mennonites, we have historically rejected the idea of the nation state and the sovereignty of kings,” says Jonathan Brenneman.

“If we read the Bible carefully, Abraham was chosen not for himself but to bless others,” says Paulus Widjaja.

“And in the New Testament, we see that these ideas are being taken and broadened to include the people of God who are followers of Jesus (1 Corinthians 6:19, 1 Peter 2:9),” adds Dorothy Jean Weaver.

“The test of whether we are faithful stewards of the land we inhabit is whether we are doing justice in the land. We need a humane theology for Israel and Palestine, a theology that recognizes the image of God and each person – in Israeli, Palestinian, Muslim, Christian, Jew. God calls people to do justice and to stand against the violence of the nation-state that mars that image of God,” says Alain Epp Weaver.

“As an Anabaptist, I seek deeply for a transnational, grassroots, non-state-based system. It’s not related to ethnicity. There’s no justification for violence in the life of any Christian because we follow one who – even in his capture by the imperial army (the cops) – said ‘it’s not coming in through violence’ and healed Malchus’ ear (John 18:10),” says Sarah Nahar.

“Reading the Bible through to Revelation, we find our call to be egalitarian, boundary-breaking groups of people who are living with integrity with deep respect for the land and each other,” she says.

“It’s a call to complexity, not simplicity. We seek to be people living without a need to control others,” says Sarah Nahar.

“White churches of European heritage inherit legacies of anti-Jewish theologies that say that God has repudiated the Jewish people. We need to examine and reject anti-Jewish theologies which have fueled antisemitism,” says Alain Epp Weaver.

“Antisemitism historically has been part and parcel of European colonialism and racism. As Anabaptists, we need to stand firmly against antisemitism as a forms of racism,” says Alain Epp Weaver.

Readers of Scripture everywhere have the same call: love mercy, seek justice, free the oppressed, release the captives, declare Jubilee (Micah 6:8),” says Jonathan Brenneman.

The answer to ‘who is chosen’ is in the Beatitudes: blessed are the peacemakers; blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness; blessed are the poor (Matthew 5:3-10).

“Blessed are those who are oppressed, basically,” says Jonathan Brenneman.

Some commentators, including human rights organizations, have referred to the Middle East today as an apartheid reality. How can Mennonites support a place where all people, Palestinian and Israeli, can sit securely under vine and fig tree (Micah 4:4)?

“It’s very hard to see what road map can chart a path from the current reality of violence and structural discrimination toward a future reality in the land in which both Palestinian and Israeli peoples can live freely, securely and at peace,” says Alain Epp Weaver.

“We pray, we support Palestinians and Israelis who are working to bring down the dividing walls that keep people from seeing each other as children of God and those dividing walls. We need to stand against the dividing walls in our hearts – and against the very physical walls erected by the Israeli state – that harm, degrade and kill people,” he says.

“We live in a world that has been divided up, where there are plots of land that some group says, ‘this is ours!’ But our calling to be faithful from wherever we are in society is to push for God’s justice on earth to the extent that we have the energy to move toward that goal as we are empowered by God: ‘your Kingdom come, your will be done on earth!’ (Matthew 6:12),” says Dorothy Jean Weaver.

“Who is responsibility for God’s will to be done on earth?” she asks. “The ultimate answer is that God is powerful over all. But God will also call us into action in bringing God’s will into existence on earth. We need to pray the Lord’s Prayer boldly and courageously.”

For those in Canada and the USA, the Mennonite Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery Coalition is helping people do the challenging work of recognizing that sin is structural.

“The tasks that I can do include understanding how dynamics of power show up everywhere; recognizing systems of displacement and dispossession; asking at what cost and whose cost I gain privilege in society,” says Sarah Nahar.

“The gospel offers a new way of thinking about our lives and encouragement to reach across barriers no matter where we are or who we are,” she says.

“In ethics, if we want our action to be meaningful, that action should be based on a narrative because otherwise the action will not be meaningful at all,” says Paulus Widjaja.

There is opportunity for those who seek meaningful narratives to ground action and understanding regarding the Holy Land. Bethlehem Bible College, an evangelical school in the heart of the West Bank, is hosting their 7th Christ at the Checkpoint conference 21-26 May 2024. “Do Justice, Love Mercy: Christian Witness in Contexts of Oppression” – an invitation to “come and see!”, in person or on livestream. (Click here to learn more.)

How can Mennonites be peaceful but not passive? When there seem to be two sides, is it possible to be neutral without implicitly siding with the oppressor?

“Neutrality is a very dangerous word for us because it allows us to imagine that things are equal and very often things are not equal,” says Dorothy Jean Weaver.

In much of the world, especially the USA, Christians are assumed to be on the side that of the military that is committing the genocide. As Christians, if we are not speaking out, we are assumed to be on the side of militarism, of violence and of genocide,” says Jonathan Brenneman.

“If we look at that question from the theological perspective, then yes, we take a side, but not on the people, certainly not on a state – we take a side on values: justice, peace, reconciliation,” says Paulus Widjaja.

The Israelites in the Bible assumed that God was always on their side, but there were times God said: ‘I’m on your side when you are oppressed, but I’m also with others when they are oppressed.’

Just look at the biblical prophets. They could never ever be accused of being neutral about the situations in which they lived,” Dorothy Jean Weaver adds.

“So I’m taking the side of the Christian principles of justice, love and reconciliation. Whoever is being oppressed, then I will be with them regardless of their nationalities,” says Paulus Widjaja.

“It’s been really meaningful to do theology out on the streets together, working for a ceasefire with Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Baha’i and humanists,” says Sarah Nahar who sees far more than two sides.

“I’ve had a chance to do theology alongside anti-Zionist Jewish people who are experiencing great grief when their beautiful, multifaceted, deep faith is being smashed on one side by nationalism and crammed in on the other by militarism,” she says.

Christians are still recovering from CE 313 when the empire took over Christianity, so we can understand people who say they don’t want a state force to be associated with who they are.

“State violence does not protect me: relationship protects me. We can have safety and space in a shared world,” she says.

“In an eschatological sense,” says Alain Epp Weaver, “there is one side, the side of humanity, the humanity God is reconciling back to God’s self through the work of the Spirit, the Spirit that breaks down walls of division and hatred.”

“For the church to witness within this broken world means speaking out against all forms of injustice, including the structures of military occupation that build walls and deepen divisions. When we speak out for justice, people will sometimes accuse us of creating division, but we are doing it animated by this vision of a reconciled humanity that God is calling back to God’s self, calling us back to our created nature,” says Alain Epp Weaver.

Palestinian Christians raised a call that was published at the end of October: “We hold Western church leaders and theologians who rally behind Israel’s wars accountable for their theological and political complicity with the Israeli crimes against Palestinians,” they wrote. (Click here to read the full document.)

“I saw and affirm that call,” says Alain Epp Weaver. “The Western Church has been complicit in the dispossession of Palestinians. And the time for speaking out in action is long overdue.”

“The wide Palestinian Christian coalition that wrote that letter are working together in significant concord with each other and they are calling the bluff of the Western Church. I pray that the Western Church has ears and heart to listen,” says Dorothy Jean Weaver.

“I’m grateful for the tradition of pacifism so we can boldly and humbly not only take stances, but do action and be in prayer with a commitment to not eliminate others,” says Sarah Nahar.

“If we are wrong, we can seek, repair and learn. I’ll carry some of these questions into our 500-year anniversary which some believe should be a celebration because we have been faithful and others think this should be a moment to grieve that our Christian body was torn,” she adds. “That is also a complex question.”

“We all continue to work and pray for wholeness in that broken part of the world and in our own broken lives,” says J. Nelson Kraybill.

Contributors

- Dorothy Jean Weaver is retired from teaching New Testament at Eastern Mennonite Seminary in Harrisonburg, Virginia, USA. She also has a long history of travel in and out of Israel-Palestine, both for academic sabbaticals and for leading study tours and work groups.

- J. Nelson Kraybill is a retired academic and former president of MWC (2015-2022). He also has long-standing involvement in Israel-Palestine both as tour leader and as an academic. He recently served as scholar-in-residence at Bethlehem Bible College in the West Bank for eight months.

- Paulus Widjaja is an ordained minister in GKMI. He is a lecturer in the faculty of theology at Duta Wacana Christian University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

- Alain Epp-Weaver directs strategic planning for Mennonite Central Committee. He lives in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, USA. He has worked in occupied Palestine for 11 years, including two years in Gaza. as program coordinator and has written and edited books related to Palestine.

- Jonathan Brenneman is a Palestinian American Mennonite. He has worked with Community Peacemaker Teams in Palestine and worked on Mennonite Church USA’s “Peace in Israel and Palestine” passed in 2017.

- Sarah Nahar currently lives in Syracuse, New York, USA (unceded Onondaga Nation land). She was the North America representative on the AMIGOS – a precursor to MWC’s YABs Committee. A former executive director of Community Peacemaker Teams, she served with Mennonite Central Committee in Jerusalem at the Sabeel Liberation Theology Centre.

Updated 16 April 2024: date of Christ At The Checkpoint conference corrected