Light and hope for those in darkness

Today, world security is threatened by international, intertribal and even interreligious conflicts. Sometimes, security forces have conflicts with the very people they are supposed to protect. Terrorism has created a climate of insecurity on the international level. Countries are torn apart by wars. Political-religious movements such as Al-Qaeda, Islamic State and Boko Haram spill blood in the name of religion. Opinions and philosophies divide people and create divided households.

Conflict undermines the basic social units of a strong and balanced society. It can cause divorce. It sends children into the street. It creates enemies within families and dissolves businesses, sending staff into unemployment.

Since its very beginning, the church has not been spared conflict, internally or externally. At the external level, the church has been and continues to be the victim of persecution. Internally, the church has always had to confront controversies and hierarchical conflicts. For example, the Anabaptists left the Protestant reform movement in the 16th century due to a conflict.

Our world, no matter how peaceful it may seem, is dominated by conflicts. How can the church in general and Christians in particular walk toward reconciliation in this contentious world? Is it possible for us to promote reconciliation in a world where conflict is gaining ground?

Analysis of 1 Samuel 25:1–35

The story in 1 Samuel 25:1–35 provides a model for walking toward conflict and from conflict to reconciliation. In analyzing this text, we can draw out practical implications that help us to grasp God’s thoughts about conflict and reconciliation.

Walking toward conflict (v. 1–13)

In verses 2–13 of the account in 1 Samuel 25, we meet Nabal, Abigail, David and messengers. Their encounters lead to a moment of opposition which turns into a conflict.

Nabal is a very wealthy man who lacks spiritual values and strength of character (v. 2–3). Nabal’s hard-heartedness is accompanied by spitefulness.

When David learns that Nabal’s sheep are being shorn, he sends some of his servants to ask Nabal for help for his group who is in the wilderness.

In his message to Nabal, David shows kindness, gentleness and humility. Militarily, he is higher than Nabal, but he uses a peaceful voice, appealing to Nabal’s sense of gratitude at a time of joy and festivities. He reminds Nabal that David’s group protected Nabal’s sheep in the wilderness.

In spite of David’s effort to approach Nabal with an attitude to promote peace, Nabal responds to David’s kindness with harshness, to his courtesy with contempt, to his confidence with disdain and hatred (v. 10–11). Nabal’s malice in the face of David’s kindness leads to conflict (v. 13) because David becomes angry and returns Nabal’s violence with violence.

We learn from these first 13 verses what are the primary factors promoting conflict in this story:

- Nabal’s harshness and malice are in opposition to the good faith and culture of peace shown by David (v.6–8). They incite the two sides to walk into conflict.

- Nabal’s selfishness leads him not only to refuse to share what he has with those in need, but also to refuse to recognize and thank those who have helped to protect his property. This is what makes David so angry that he decides to teach this man a lesson with violence.

- The contact between David and Nabal is handled by messengers who also play an active role in this conflict. The way in which they give information also contributes to the explosion of conflict.

The factors promoting conflict in this passage are the same today. How can the church promote peace in such circumstances?

From conflict to reconciliation (v. 14–35)

The second section of our story begins another sequence of events. The principal actors are Nabal’s servant, Abigail and David.

Nabal’s reaction does not leave his team indifferent. Nabal’s servants disapprove of the way he acts and expect reprisals from David and his servants. A prudent man, who sees danger and hides (Proverbs 22:3; 27:12), one servant helps his mistress to understand the situation. He proposes a way to get around their master, whose character could not allow him to accept reconciliation that brings peace (v. 17).

Abigail listens well. Her approach to the situation demonstrates courage, tact and humility (v. 18–20). Her peaceful strategy is built around a team working for peace (v. 19). She faces up to conflict with a peaceful plan (v. 20), all the while managing obstacles to peace (v. 19). She asks for forgiveness without embarrassment, and offers to meet needs and calm spirits.

What lesson can we learn from the way in which this woman models conflict resolution, and from the process she uses to achieve reconciliation?

Reconciliation, the path to conflict resolution

God does not want his children to participate in conflicts, but wants them to work for peace (Ephesians 4:1–3) as Abigail does. She follows a path of reconciliation which gives up hostility and re-establishes civility and communion between formerly hostile parties.

Reconciliation is an urgent need in our world. We need to re-establish communion between God and humanity (Romans 5:8–11; 2 Corinthians 5:18–19; Colossians 1:19–22); between human beings (Ephesians 2:11–22) and to reestablish harmony in the entire creation (Romans 8:18-22).

Hope for our reconciliation is rooted in the work of Christ on the cross, which wiped out God’s anger and judgment of humanity. The cross of Christ provides for reconciliation. On the cross, Christ erased the act which condemned us and triumphed over the hostility and all the cultural barriers which separated us (Colossians 2:14–15).

The work of the cross gives us peace and justice – not just for the church, but for the entire world. We are called not only to believe in peace and justice, but to apply them to all without distinction or discrimination, and to promote them to the entire world through the proclamation of the good news of salvation.

Following the example of Christ, the church must work for love, peace and justice in spite of the price which must be paid (Isaiah 11:1–5; 61:1–3; Luke 4:13, 19). The church must demonstrate compassion by its ability to see and to hear the cry of the oppressed and to identify with just causes. It is only God who reconciles us with himself by sacrificing Jesus on the cross, the pivot point of reconciliation.

Reconciliation between humans is rooted in Christ who is the peace of the world (Ephesians 2:14–17) and the source of unity for all humanity (John 17:11, 22, 23).

Reconciliation passes through the resolution of conflicts, not only on the personal level, but also at the ethnic and tribal level, and at the level of the church.

Conflict resolution at the personal level

The Word of God teaches us that the best way to resolve conflicts is on the personal level. This involves confession before God of all sins we are aware of (1 John 1:9–10; Psalm 139:23–24) and commitment to asking for forgiveness and deciding not to repeat the same fault (Ephesians 4:32; James 5:16).

The Gospels propose this process for us:

- Pray sincerely to God and ask for forgiveness;

- Speak alone with the other person;

- Speak with the other person in the presence of two or three people;

- Speak with the other person before the church (Matthew 18:15–17).

A desire to honour God and love for the other person are necessary for conflicts to be resolved (Psalm 34:15). We must always seek divine help and ask for wisdom, self-control and appropriate speech (Proverbs 16:32; James 1:5).

In addition, we must use the rules for good communication: listen to the other person, state the truth, speak in a fair way with love, express ideas clearly and speak with integrity for the glory of God and the well-being of the other person. The objectives for this good communication are to resolve the problems which led to the conflicts. End meeting times with prayer and with words of fraternity or kindness (James 3:13–18).

Conflict resolution at the ethnic, tribal and racial level

Ethnic, tribal and racial conflicts are often the shame of the church. Our silence seems to be a form of complicity to such an extent that today, wise thinkers accuse the church of creating or participating in this kind of conflict, such as the history and heritage of racism and the slave trade, the Holocaust, apartheid, ethnic cleansing, discrimination against native populations, interreligious/political/ethnic violence, the suffering of the Palestinians, caste oppression and tribal genocide.

In the face of this situation, I call on pastors, church leaders and all readers to teach the biblical truth about ethnic diversity, but also to acknowledge the concept of sin in these ethnic groups. In Christ, all our ethnic identities are subordinated to our identity as assets purchased at the cross. In practical terms, the church must:

- Prioritize healing and reconciliation: In case of aggression, self-defense is permitted, but not the use of violence. Following the example of Jesus, who did not use weapons when threatened, the church must walk in the steps of the master. The church must demonstrate the attitude of caring for its enemies as illustrated in the parable of the good Samaritan, and practice nonviolence as the door to reconciliation.

- Promoting justice is an important way to reduce ethnic and religious conflicts in the world. To do this, the church must become deeply involved in standing up to injustice, to ethnocentrism, to racism and to oppression. It must get involved in reconciliation and identify itself with the oppressed, working for justice for them.

- Develop an inclusive church: The church cannot be a site for ethnic divisions and racial discrimination; rather it must be a setting where all are invited and taken into fellowship. Leaders must not be selected on criteria that favour ethnicity or race over spirituality. The church must not have an ethnic agenda. It is an entity of “unity in diversity” where all members are one in Christ as taught in Galatians 3:28. The church is a new ethnic group in which there is mutual protection and security for everyone.

- Guide our approach to politics and to management of public property with Christian principles: Political opinions must not be molded by ethnic, tribal or racial prejudices but by Christian principles. Christians who are politicians must deal correctly with everyone without prejudice based on political or religious ideology. Politicians must avoid ethnic favouritism and religious fanaticism, which often encourage hatred.

- Practice love and forgive enemies: Praying for enemies is one of the signs of obedience and submission to Jesus Christ. We must love other people because they are created in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 9:6; James 3:9). Forgiveness is often very difficult to give, especially when we are victims of injustice, hatred and oppression. But we must be willing to obey the Word of God.

Conflict resolution in the church

The walk toward reconciliation requires the church to obey scriptural principles and to defend them to the world through the way it lives. It must display transparence by relying on biblical teachings. The church must continue to count on God’s help so that it can resolve conflicts more effectively. It must avoid lack of respect for its own legal and juridical texts.

The church must avoid favouritism. In its prophetic role, it must be watchful and active to

- Always pull itself back to God’s will, commandments and precepts, and tell the world about those things.

- Discover the true nature of the problems in the church and in the world by deeply studying the causes, motives, sources and origins both near and far, in order to propose solutions without taking sides.

- Look for peaceful solutions and stand up to the sinful politics of exclusion and marginalization. The church must prioritize political systems which promote unity and reconciliation.

The reconciliation of people with creation

We must be people who take care of creation, because reconciliation also includes creation. Human life and creation are linked together because the earth takes care of us (Genesis 1:29–30); the earth suffers with us because of humanity’s sins which have caused heavy consequences (Hosea 4:1–3); God’s redemption includes creation (Psalm 96:10–13); everything was reconciled at the cross (Colossians 1:15–23); and the good news includes all of creation.

In light of this state of affairs, the church in general and Christians in particular must be on the frontlines of the efforts to protect creation. We must have a great desire to live on a green planet by avoiding the waste of energy, by reducing our use of carbons, by recycling our environment and by avoiding pollution.

In the same vein, we must support political and economic initiatives which protect the environment from all kinds of destruction. So we must support those among us who are called and sent by God with a special mission to protect the environment, and to do scientific research in the fields of ecology and nature conservation.

Conclusion

Violence has been used in many different ways to resolve the incessant conflicts throughout the world. But history proves that has not succeeded in bringing solutions to the problems of the world. The way of violence promises hatred, anger and vengeance instead of peaceful resolution for conflict.

Indeed, nonviolence is the ultimate solution to conflicts. Christ was nonviolent when confronted by conflicts. He outlines for us the model which we should use when resolving conflicts.

The nonviolent model for resolving conflicts, as we have discovered in the story about Abigail, is not synonymous with passively accepting injustice and aggression without protecting ourselves. It means we do not use force as a means of resolving conflicts.

The church must actively resist religious and ethnic conflicts. Only love for the enemy and the determination not to use force or violence can withstand conflicts and peacefully engage the enemy. This eliminates the structures of injustice and replaces them with good structures that have God at the centre.

Ethnic diversity is the gift and the plan of God in creation. It has been dirtied and deformed by human sin and pride which produce confusion, quarrels, violence and wars between nations.

However, this diversity will be preserved in the new creation when people from all nations, from all tribes, from all the people groups and all the languages will be reunited because they make up the people whom God has redeemed.

Because of the gospel, I ask the body of Christ collectively and individually to repent and to ask forgiveness in all places where they have participated in violence, injustice and ethnic oppression.

Today, the church must embrace the great power of reconciliation found in the gospel, and really learn about it, because Christ did not carry our sins on the cross only so that we would be reconciled with God, but also to destroy our animosities and so that we can be reconciled with each other.

Let us adopt a reconciliation style of life by forgiving those who persecute us and having the courage to expose the injustice they cause to others. Let us provide aid and offer hospitality to those on the other side of a conflict by taking the initiative to cross barriers to achieve reconciliation. Let us continue to witness about Christ in violent contexts, always ready to suffer or even die, rather than participate in acts of destruction or vengeance. Let us get involved in the long process of healing wounds, making the church a safe place of healing for all, including old enemies.

We must be a bright light and a source of hope. We must share this witness: “God in Christ, reconciling all people to himself.” The cross and the resurrection of Christ grant us the authority to confront the demonic powers of evil which exacerbate human conflicts.

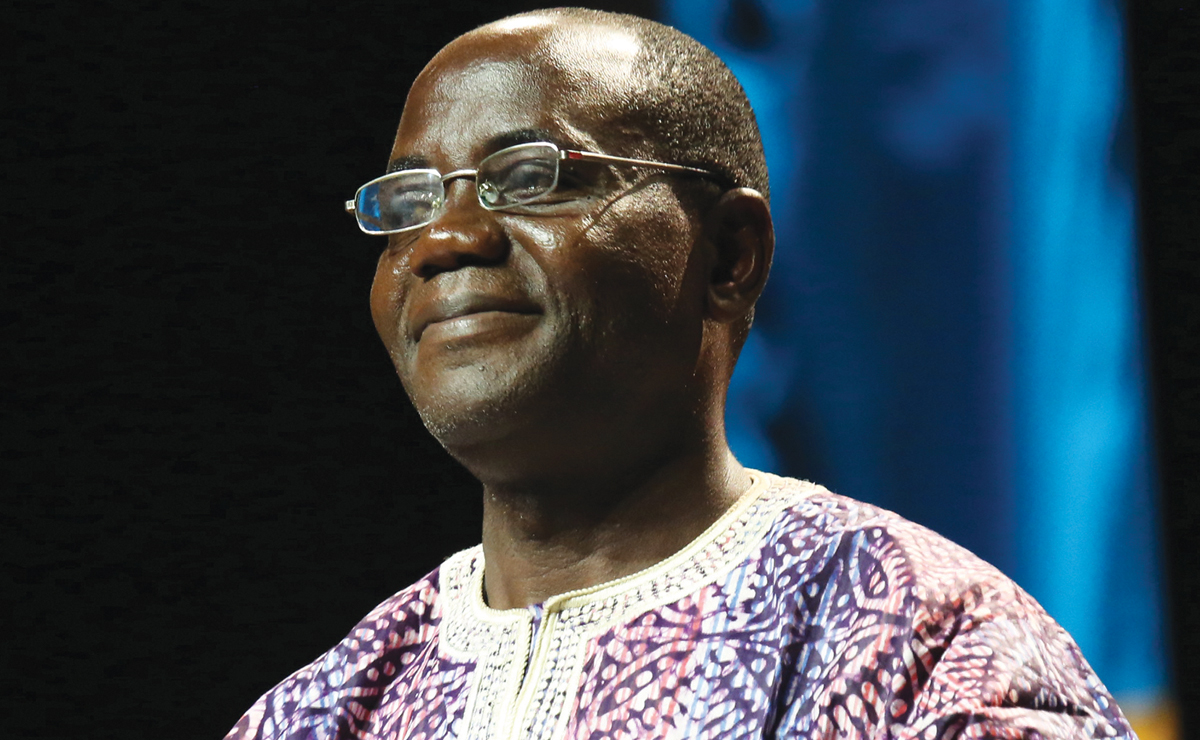

Nzuzi Mukawa of the Democratic Republic of Congo spoke on Thursday evening, 23 July 2015 at Assembly 16. Nzuzi is the team leader for MB Mission in sub-Saharan Africa. He is both a professor of missions and an associate pastor of a Mennonite Brethren congregation in DR Congo.